Global beverages: games without frontiers

RBC Capital Markets’ Consumer Staples Equity Research Team argues that the beverage industry is at an inflection point, in an RBC Imagine report - research where it looks beyond the normal forecast horizon. RBC uses game theory to consider whether the spirits companies have had it all their own way and how the big brewers’ fight-back will address that imbalance.

Losing the plot

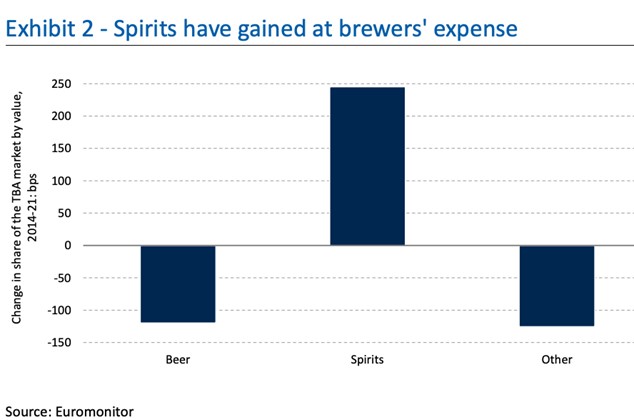

RBC first points out that brewers’ fixation with industry consolidation has allowed their spirits counterparts to enjoy strong category growth and win significant market share of the alcohol category. It has also created a perception invincibility around the spirits companies and the also-run nature of beer.

However, with new CEOs at AB InBev and Heineken both concentrating on their existing businesses and nurturing the beer category, RBC expects the brewers’ financial and operational performance to improve and consequently their valuation discount compared to the spirits companies to narrow.

Game theory and the brewers: the prisoner’s dilemma

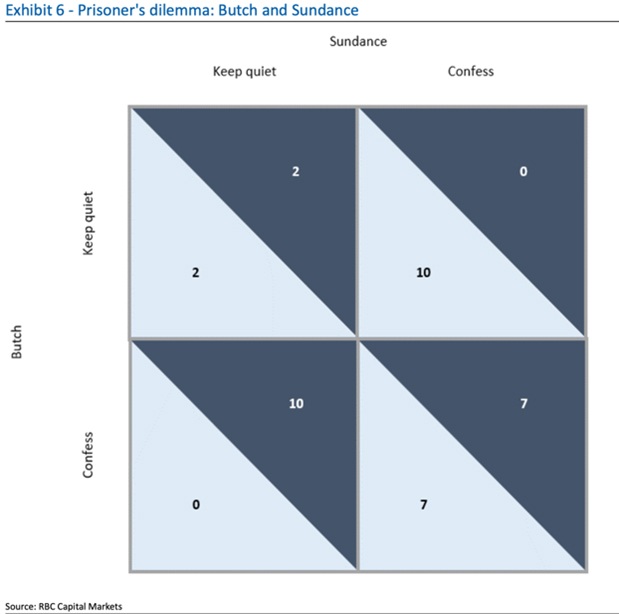

Game theory was originally developed in a 1944 book ‘The theory of games and economic behaviour’ by John van Neuman and Oskar Morgenstern. The idea was to see how participants in a dynamic ‘game’ will behave in the knowledge that their opponents are also adapting their own behaviour to ensure an optimal outcome. Perhaps the best known and most widely quoted example of game theory is the prisoner’s dilemma. It essentially illustrates how two protagonists in a game can contrive the worst possible outcome while both are behaving logically in pursuit of their own interests.

Here is an example:

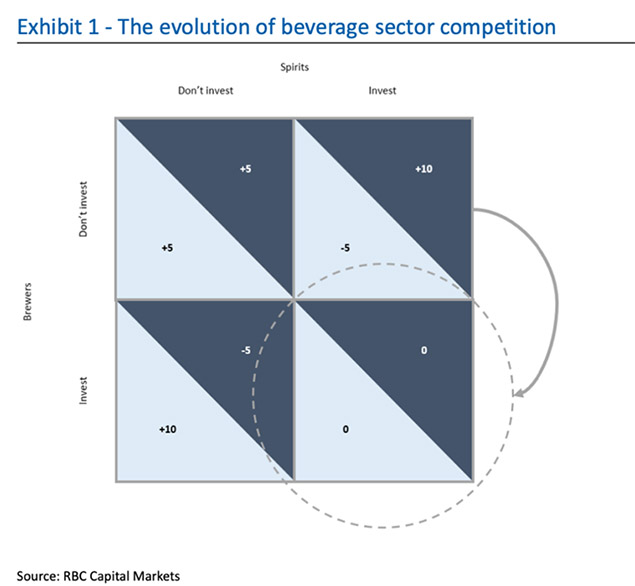

Assuming the market comprises just two companies, X and Y, if both companies invest, the result is a neutral outcome.

If company X decides to increase marketing investment but company Y, doesn’t: X will expect to gain share at the expense of company Y. Operational gearing will kick in and company X will have started its pursuit of the virtuous circle. The reverse is true for company Y of course, which will suffer the consequences of declining market share, rising cost ratios and margin pressure.

If neither company invests, market shares remain static, market growth falters slightly but that is more than offset for both companies by the P&L benefit of a flat or declining marketing/sales ratio. While it’s not as good as stepping up investment when your competitor doesn’t, it is better for short term profitability than both companies stepping up investment.

What ought to have been a classic prisoner’s dilemma, whereby it’s in everyone’s interest to invest to grow their business, has become one where the spirits companies have upped revenue investment and the brewers have rolled over, RBC argues.

The brewers need to start trying

RBC believes more marketing is generally a good thing for sales growth over time assuming the companies have competent marketing teams, brands that are receptive to marketing investment and are all similarly efficient in their management of the marketing function.

While there’s clearly a lot more to driving revenue growth than throwing money at marketing, the team stresses that it is hard to escape the conclusion that it works (L'Oréal and Campari are the best examples of this). RBC thinks the brewers’ reversals of their persistent cuts in marketing investment is an essential pre-condition of them rediscovering their financial and share price mojo.

This means that the brewers’ share price underperformance relative to the spirits companies has been to an extent self-inflicted; and it lies within the brewers’ power to at least partly reverse it.

To conclude, given the beer and spirits companies’ respective valuations, RBC has a clear preference for the former over the latter. Not because the brewers can flick a switch and suddenly perform much better than the spirits companies, but by eschewing the self-harm that they’ve inflicted on themselves through a lack of care and attention to their existing businesses, the two sub-sectors should perform much more comparably in future.