Financial markets are in a state of disruption, impacted at both a macro-economic and company level. Among these disruptions, protectionism has been a particularly central force, with some countries trying to deepen international trade while others undermine it. RBC Wealth Management took a closer look at these unfolding conditions and what this could mean for tariffs and the US dollar.

Just how bad might the “year of the tariff” turn out to be? RBC Global Asset Management’s chief economist Eric Lascelles looks at the various nations implicated in trade negotiations and tallies up the good, the bad, and the ugly.

The Year of the Tariff

This article was originally published by RBC Wealth Management.

Protectionism is back in play, and we assess the potential outcomes—good, bad, and ugly.

Financial markets are in a state of high alert, responding spasmodically to an onslaught of macro- and company-level shocks. Among them, protectionism has been a particularly central and recurring villain. Just how bad might the “year of the tariff” turn out to be? RBC Global Asset Management’s chief economist Eric Lascelles tallies up the good, the bad, and the ugly.

The good

There are two sides to every ledger, and—believe it or not—some countries are still trying to deepen international trade rather than undermine it. The recently announced 11-nation Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) trade pact is a major step forward. The EU has also entered into important deals with Canada and Japan.

China, the world’s other superpower, is opportunistically seeking to fill the void left by a retreating U.S. Doing so includes a gradual tempering of Chinese capital controls and a vision of China as the benefactor of a refreshed Marshall Plan, connecting (and enriching) central Asia and eventually much of the developing world via large-scale infrastructure projects.

NAFTA negotiations, so far a long, grim affair, have suddenly bounded forward after the U.S. surprisingly eased its demands on the minimum domestic share of auto production. No less importantly, the comments from all three countries have suddenly become much more constructive, with each appearing to target a high-level deal this month.

Granted, there is more NAFTA work to be done. Key sticking points include a proposed sunset clause, the nature of the pact’s dispute resolution system, and government procurement rules. It remains unclear what concessions Canada and Mexico have made. Furthermore, there could yet be a last-minute hitch (whether premeditated by U.S. negotiators or via a wrench thrown by the executive branch). But suffice it to say that whereas we rated the risk of NAFTA’s destruction as high as 40 percent at one point, in our assessment it has fallen to just 15 percent. That doesn’t guarantee the final deal is economically positive or even benign, but it does limit the damage.

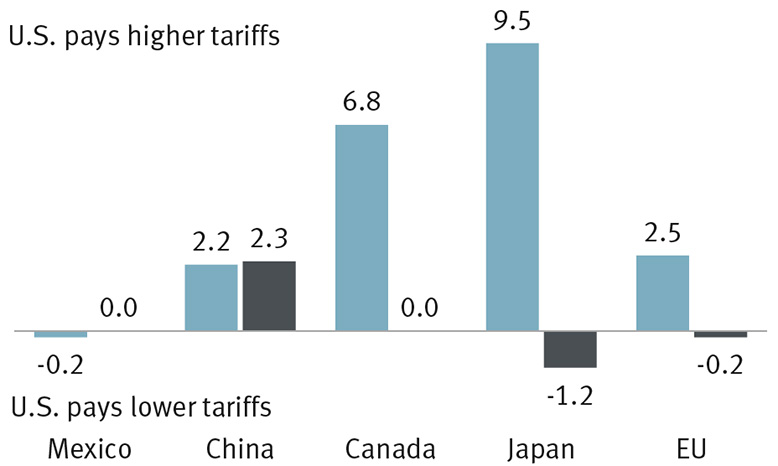

Let us also recognize that the U.S. is not entirely incorrect in its trade grievances. American exporters do, on average, pay higher tariffs than foreign firms do when entering the U.S. market. If the recent barrage of U.S. tariffs is instead viewed as being a temporary wedge designed to pry open foreign markets, globalization could actually be advanced rather than impeded by these unorthodox tactics. This is unquestionably a best-case interpretation, but not an impossible one based on White House comments. In fact, there is some evidence of the U.S. succeeding with this approach in the past:

U.S. gets bad tariff deal versus partners

Tariff rate differential between U.S. and partner countries, 2017 (ppt)

U.S. trade complaints not without some foundation.

Note: Difference between tariff rates U.S. pays on its exports to partner countries and rates partner countries pay on exports to U.S. Source - WTO/ITC/UNCTAD World Tariff Profiles 2017, RBC Global Asset Management, RBC Wealth Management

- President Nixon imposed a blanket 10 percent tariff on imports in 1971, removing it four months later when other countries agreed to depreciate their exchange rates against the U.S.

- The Plaza Accord of 1985 was not technically a protectionist action, but the currency negotiations therein were motivated in part by U.S. firms agitating for trade protection. Instead, the world’s major nations agreed to devalue the dollar and, in so doing, obviate the need for damaging protectionist actions.

- Across the 1980s, President Reagan implemented a number of tariffs and import controls. These did not seriously interfere with economic growth, were eventually lifted, and prompted Japanese automakers to shift more of their production onto U.S. shores.

Lastly, it is some relief to learn that recently proposed trade barriers are set to inflict surprisingly little economic damage, according to most estimates. For instance, based on the actions taken so far, the trade spat between the U.S. and China will cost each economy less than a quarter of one percent of their economic output. The effective U.S. tariff rate on imports will rise from just 1.6 percent to 2.1 percent—a far cry from an average tariff rate above 20 percent for much of the 1920s and 1930s. The world is still a much friendlier place to trade now than at almost any other point in time.

The bad

Whenever protectionism is in play, there is also going to be a considerable amount of “bad” news.

First, protectionism has long since morphed from words into action, with U.S. tariffs now in place on softwood lumber, washing machines, solar panels, steel, and aluminum. As much as President Trump promised and then delivered tax cuts, he is now clearly acting upon his protectionist mandate. The odds of further action are hardly trivial given the extent to which his more moderate advisors have fallen by the wayside.

Second, the latest Chinese tariffs are much more significant than anything that has come before, in part because of the size of the tariffs—a 25 percent tax on $50B of imports—and in part because China is proving to be an equally pugilistic adversary. Based on the orientation of the tariffs to date, on U.S. agricultural products versus Chinese technological products, the U.S. may take a disproportionate share of the economic hit this round because agricultural products can be more easily replaced than specialty manufactured goods. But Chinese vulnerability is ultimately significant given that the country exports three times as much to the U.S. as the other way around.

Third, U.S.-China antagonism is hardly brand new. The two have been scrapping over control of the Pacific for some time. Foreign direct investment between the two fell by one-third last year and appears on track to decline further this year. Such frictions are unsurprising—the transition from a hegemonic to a multipolar world classically results in friction between the ebbing and ascending nations.

Fourth, even for aggrieved countries that seek redress through the proper channels—filing a dispute with the World Trade Organization (WTO)—any remedy is typically slow to come and the medicine might just be worse than the disease. The complainant is often told by the WTO to impose its own tariff on the “trade bully.”

Fifth, both the U.S. and China have taken to ignoring the WTO anyway, threatening to undermine the existing scaffolding of global trade. While U.S. courts and Congress could try to impede the president’s trade actions, the laws of the land grant him extensive powers that would be hard to neutralize.

Sixth, the U.S. is even further off the globalization course than its recent tariffs would suggest. On a counterfactual basis, it has also failed to sign on to several deals that were previously full steam ahead, including the aforementioned TPP and a deal with Europe. True, President Trump spoke recently of rejoining the TPP, but that is not a realistic aspiration given the concessions he would demand.

Seventh, the protectionist trend is not limited to the U.S. The British decision to flee the EU is another prominent example. Subtly, quite a number of countries have also been skirting trade rules by fortifying their non-tariff barriers. This appears to be the newest trick in the protectionist arsenal. With tariffs and import quotas now frowned upon, countries have found more subtle ways to give a (Pyrrhic) victory to the home team.

Eighth, and turning to Canada, the prospect of a NAFTA deal, even a slightly sour one, is undeniably a marked improvement on expectations from just a month ago. But it does not get Canada completely off the “bad competitiveness” hook, which has even more to do with divergent tax policy, labour laws, and the broader regulatory environment.

The ugly

Our best guess is that protectionism will merely act as a pesky drag on global growth, avoiding outright economic carnage.

But alternate scenarios abound, and one must acknowledge something like a 20 percent chance of a rather uglier outcome—a full-blown trade war. This might not be outright recessionary based on the modelling done to date, but it could certainly suck all of the juice out of recent U.S. tax cuts.

The scenario goes as follows: It is far from clear that the U.S. is done conjuring up Chinese tariffs. To the contrary, the tariffs thus far merely respond to China’s steel glut and the country’s questionable intellectual property practices. China can also be accused of subsidizing and shielding a slew of other sectors.

From a broader perspective, China is responsible for much of the gaping U.S. trade deficit that the White House finds so objectionable. President Trump is already threatening another round of Chinese tariffs that would be twice as big as the prior round. And while it takes two to wage a trade war, China has proven its willingness to punch back.

Bottom line

To reiterate, a trade disaster should not be anyone’s base case. Given a number of positive tailwinds still blowing from other points on the compass, the global growth story looks capable of surviving a modest trade drag. U.S. dalliances with protectionism in the 1970s and 1980s ultimately did little damage, and there is still the chance that U.S. pressure manages to dismantle some foreign barriers.

But one cannot speak with precision about these things, and the potentially deleterious effects of second-order considerations such as uncertainty and skittish financial markets are hard to model. We are inclined instead to acknowledge this threat by flagging protectionism, alongside an aging business cycle (for what it’s worth), as the key macro risks for the coming year at least.

Sign up to receive weekly economic updates from Eric Lascelles.

Required disclosures

Research resources

Non-U.S. Analyst Disclosure: Eric Lascelles, an employee of RBC Wealth Management USA’s foreign affiliate RBC Global Asset Management Inc.; contributed to the preparation of this publication. This individual is not registered with or qualified as a research analyst with the U.S. Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (“FINRA”) and, since he is not an associated person of RBC Wealth Management, he may not be subject to FINRA Rule 2241 governing communications with subject companies, the making of public appearances, and the trading of securities in accounts held by research analysts.

This publication has been issued by Royal Bank of Canada on behalf of certain RBC ® companies that form part of the international network of RBC Wealth Management. You should carefully read any risk warnings or regulatory disclosures in this publication or in any other literature accompanying this publication or transmitted to you by Royal Bank of Canada, its affiliates or subsidiaries.

The information contained in this report has been compiled by Royal Bank of Canada and/or its affiliates from sources believed to be reliable, but no representation or warranty, express or implied is made to its accuracy, completeness or correctness. All opinions and estimates contained in this report are judgements as of the date of this report, are subject to change without notice and are provided in good faith but without legal responsibility. This report is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any securities. Past performance is not a guide to future performance, future returns are not guaranteed, and a loss of original capital may occur. Every province in Canada, state in the U.S. and most countries throughout the world have their own laws regulating the types of securities and other investment products which may be offered to their residents, as well as the process for doing so. As a result, any securities discussed in this report may not be eligible for sale in some jurisdictions. This report is not, and under no circumstances should be construed as, a solicitation to act as a securities broker or dealer in any jurisdiction by any person or company that is not legally permitted to carry on the business of a securities broker or dealer in that jurisdiction. Nothing in this report constitutes legal, accounting or tax advice or individually tailored investment advice.

This material is prepared for general circulation to clients, including clients who are affiliates of Royal Bank of Canada, and does not have regard to the particular circumstances or needs of any specific person who may read it. The investments or services contained in this report may not be suitable for you and it is recommended that you consult an independent investment advisor if you are in doubt about the suitability of such investments or services. To the full extent permitted by law neither Royal Bank of Canada nor any of its affiliates, nor any other person, accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or the information contained herein. No matter contained in this document may be reproduced or copied by any means without the prior consent of Royal Bank of Canada.

Clients of United Kingdom companies may be entitled to compensation from the UK Financial Services Compensation Scheme if any of these entities cannot meet its obligations. This depends on the type of business and the circumstances of the claim. Most types of investment business are covered for up to a total of £50,000. The Channel Island subsidiaries are not covered by the UK Financial Services Compensation Scheme; the offices of Royal Bank of Canada (Channel Islands) Limited in Guernsey and Jersey are covered by the respective compensation schemes in these jurisdictions for deposit taking business only.

Despite heightened trade uncertainty, currency markets seem to be taking recent developments in stride. Laura Cooper, Head of FX Strategy & Solutions at RBC Wealth Management, looks at how protectionism, recent trade tensions and economic growth conditions outside of the US raise uncertainties for the US dollar.

The US Dollar in an Era of Protectionism

This article was originally published by RBC Wealth Management.

While protectionism raises uncertainties for the dollar’s nascent recovery, we think the dollar will be able to navigate the cracks in its newly formed floor.

Despite heightened trade uncertainty, currency markets seem to be taking recent developments in stride. Currency market volatility is sitting at multi-month lows. The dollar has waded through the tensions of the past few months, trending broadly sideways against a basket of currencies. What negative U.S. dollar sentiment remains appears to stem from external factors, namely improved economic growth conditions outside of the U.S., and financial market caution around the extent to which the Federal Reserve will raise rates.

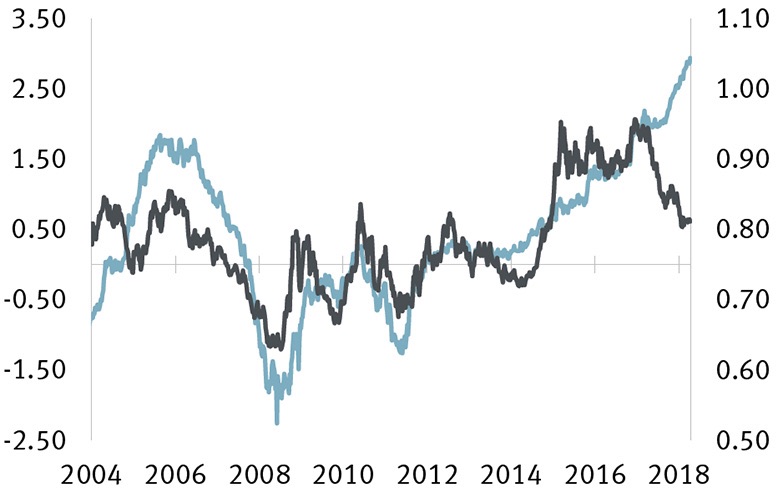

Sentiment has seen the dollar break away from traditional drivers

Negative sentiment has contributed to a breakdown between the dollar and its relationship with interest rates.

Source - RBC Wealth Management, Bloomberg; data through 4/13/18

Recent trade tensions, in our view, largely reflect posturing with an easing of the aggressive tone likely to prevail and a global trade war unlikely to occur. This would allow for a renewed focus on a backdrop of strengthening economic growth, moderately rising inflation, and a gradual tightening of monetary policy, all of which would support the dollar finding a floor in 2018.

However, the confluence of factors at play in the current environment—notably, the injection of fiscal stimulus at a time of economic strength and a widening in the trade and budget deficits, all amidst Fed tightening—warrants a closer look at what protectionism could mean for the dollar.

Trade snapshot

The U.S. runs a large trade deficit with the rest of the world, with the bulk of the imbalance coming from trade with China, followed by Germany and Mexico. Importantly, a trade deficit does not naturally confer a position of economic weakness upon a country. A stronger economy with falling unemployment and rising incomes positions consumers to afford a greater amount of goods, both domestic and imported.

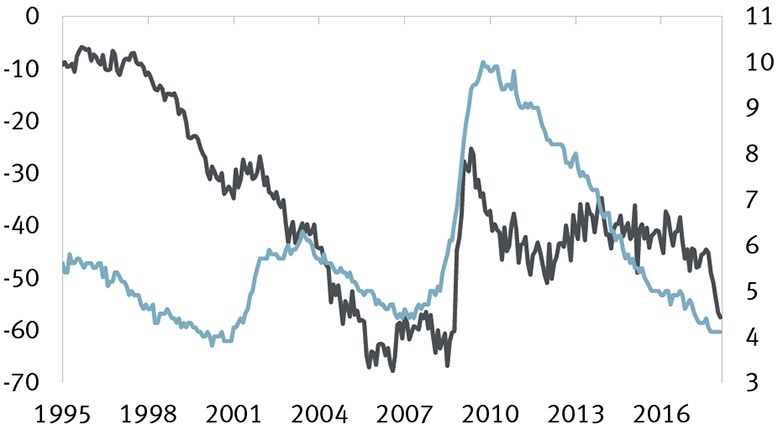

Strong labour market enables consumers to afford a greater amount of goods

A stronger economy with rising household incomes positions consumers for higher spending, both domestic and imported.

Source - RBC Wealth Management, Bloomberg; data through 3/31/18

Tariffs are not a panacea

If a country buys more goods and services from the rest of the world than it sells, it must effectively “borrow” from abroad to pay for the purchases. It does this by selling financial assets such as stocks, corporate bonds, and government securities (Treasuries) to foreigners, and then uses the proceeds to fund the extra goods and services it wishes to purchase. The currency exchange rate ensures that demand for investment funds balances with the flow of goods and services.

Tariffs distort this process. Goods entering a country become more expensive as the extra cost from the tariff (tax) can be passed on to consumers. While the rationale behind tariffs is to shift demand towards relatively cheaper domestically produced products and thereby stimulate domestic sectors, in practice, this is often not the outcome. Trade deficits are typically little changed following the imposition of tariffs.1

The recent U.S. tariffs on steel and aluminum are likely to have only a negligible effect because of the small size of these industries relative to the U.S. economy. However, a tit-for-tat escalation could leave the Fed weighing the inflationary impact of tariffs against the need to not stifle economic growth. The net effect could be increased interest rate policy uncertainty, which would likely constrain the dollar.

A unique position

The savings and investment behaviours of countries tend to play a greater role in trade balances than trade policy alone. Countries with a surplus of domestic savings, like China, which save more than they invest within their own borders, essentially “lend” the excess funds to countries abroad by purchasing foreign assets, such as U.S. Treasuries. This, in turn, provides a surplus of funds for the U.S. to purchase foreign goods, resulting in a current account deficit (includes goods and services and net income/transfers from abroad). Appetite for U.S. Treasuries remains strong amongst China, Europe, and Japan, and the inflow of foreign capital enables the U.S. to fund its current account deficit.

A sizeable sale of foreign holdings of U.S. Treasuries—China is the largest holder—would likely spur higher U.S. interest rates and tighter financial conditions, slowing U.S. economic activity and dragging down the dollar. This is not our base-case scenario, but it presents a meaningful risk, which highlights the threats posed by retaliatory tariff actions and the potential knock-on effect to U.S. assets. These could further weigh on already negative dollar sentiment.

Add a larger budget deficit to the mix

The added challenge in the current environment is that the U.S. federal budget (fiscal) deficit is almost certain to widen given the implementation of tax cuts, and would increase further if an infrastructure spending program is passed. With a reliance on capital from China and other countries to cover part of this budget shortfall, all else equal, this implies a larger U.S. current account deficit.2

Another concern of markets is that the current fiscal injection is coming at a time when economic momentum is strong and surplus capacity is rapidly diminishing, potentially overheating the U.S. economy.

At the same time, heightened uncertainty around protectionist objectives could cause investors in U.S. securities to demand to be compensated for taking that extra risk, potentially making U.S. financial assets less attractive to some foreign investors.

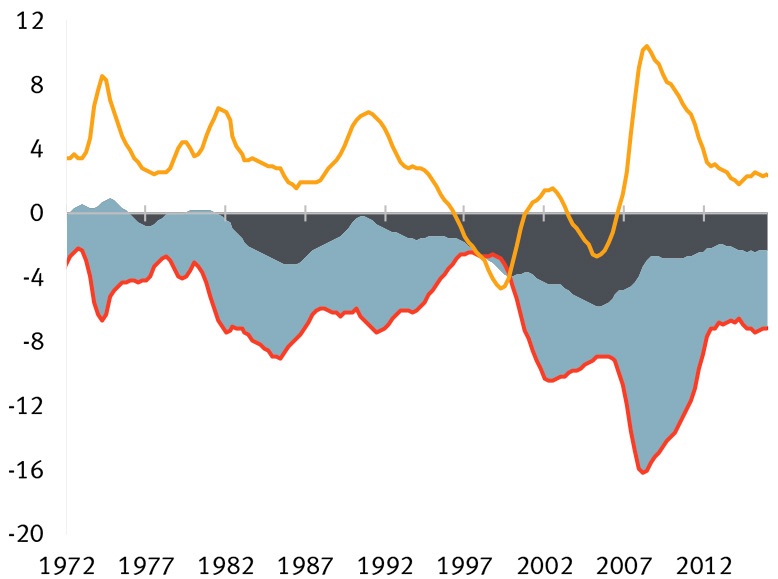

Historically, the dollar’s performance has been mixed under conditions of rising trade and fiscal deficits, and largely dependent on the actions of the Fed. In the current environment, the fiscal deficit may be less problematic for the dollar. Private savings from households could provide some offset to rising fiscal deficits given the relatively better financial position of households compared to previous periods. This alongside a Fed that has signaled it could raise rates beyond current market expectations could limit the dollar downside against a protectionist backdrop.

Widening deficits may be less problematic for the dollar this time around

Private savings from households could get a lift from tax cuts, providing some offset to rising fiscal deficits.

Source - RBC Wealth Management, Bloomberg

Dollar recovery intact

Confidence in the economic outlook saw the Fed raise its key interest rate in March, for the sixth time this recovery cycle. The Fed’s optimism about the economic expansion led it to adopt a modestly higher rate hike forecast path beyond 2018. The robust economy, augmented by fiscal stimulus, argues for an uptick in inflationary pressures, which could provide scope for the Fed to raise rates somewhat faster than currently planned. Were that to occur, it would provide an additional tailwind to the nascent dollar recovery.

More aggressive protectionist and tariff strategies by the U.S. administration and its trading partners could, however, add a layer of uncertainty to this outlook. First, a potential exodus of capital flows from the U.S. at a time when the country will need to rely on these funds to finance ballooning deficits would inevitably be dollar-negative. Second, a more cautious Fed on account of a clouded economic outlook related to trade uncertainty could also weigh on dollar performance.

While protectionism raises these and other uncertainties, our view remains that the dollar will navigate these cracks in its newly formed floor. The trade disputes are ultimately likely to be handled reasonably and rationally, rather than degenerate into aggressive back-and-forth implementations of tariffs across a wide range of goods.

1 Consensus points to tariffs being inflationary; they can push up the prices of imports with the resulting rise in demand for domestic goods spurring higher prices as well. The higher import prices effectively lower demand for imports. This implies less demand for foreign funds used to pay for the goods. The domestic currency strengthens as a result, and a country’s goods become relatively more expensive for the rest of the world, leading to an export pullback. On net, theory suggests that the trade balance would thus be little affected by tariffs, yet volumes would be lower and consumers would face higher prices.

2 U.S. Net Saving = minus Rest of World Net Saving; so a decline in the government budget balance (decline in U.S. net saving) must correspond with a decline in the U.S. current account or equivalently a rise in net borrowing from the rest of the world.

Required disclosures

Research resources

Non-U.S. Analyst Disclosure: Laura Cooper, an employee of RBC Wealth Management USA’s foreign affiliate Royal Bank of Canada Investment Management (U.K.) Limited; contributed to the preparation of this publication. This individual is not registered with or qualified as a research analyst with the U.S. Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (“FINRA”) and, since she is not an associated person of RBC Wealth Management, she may not be subject to FINRA Rule 2241 governing communications with subject companies, the making of public appearances, and the trading of securities in accounts held by research analysts.

This publication has been issued by Royal Bank of Canada on behalf of certain RBC ® companies that form part of the international network of RBC Wealth Management. You should carefully read any risk warnings or regulatory disclosures in this publication or in any other literature accompanying this publication or transmitted to you by Royal Bank of Canada, its affiliates or subsidiaries.

The information contained in this report has been compiled by Royal Bank of Canada and/or its affiliates from sources believed to be reliable, but no representation or warranty, express or implied is made to its accuracy, completeness or correctness. All opinions and estimates contained in this report are judgements as of the date of this report, are subject to change without notice and are provided in good faith but without legal responsibility. This report is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any securities. Past performance is not a guide to future performance, future returns are not guaranteed, and a loss of original capital may occur. Every province in Canada, state in the U.S. and most countries throughout the world have their own laws regulating the types of securities and other investment products which may be offered to their residents, as well as the process for doing so. As a result, any securities discussed in this report may not be eligible for sale in some jurisdictions. This report is not, and under no circumstances should be construed as, a solicitation to act as a securities broker or dealer in any jurisdiction by any person or company that is not legally permitted to carry on the business of a securities broker or dealer in that jurisdiction. Nothing in this report constitutes legal, accounting or tax advice or individually tailored investment advice.

This material is prepared for general circulation to clients, including clients who are affiliates of Royal Bank of Canada, and does not have regard to the particular circumstances or needs of any specific person who may read it. The investments or services contained in this report may not be suitable for you and it is recommended that you consult an independent investment advisor if you are in doubt about the suitability of such investments or services. To the full extent permitted by law neither Royal Bank of Canada nor any of its affiliates, nor any other person, accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss arising from any use of this report or the information contained herein. No matter contained in this document may be reproduced or copied by any means without the prior consent of Royal Bank of Canada.

Clients of United Kingdom companies may be entitled to compensation from the UK Financial Services Compensation Scheme if any of these entities cannot meet its obligations. This depends on the type of business and the circumstances of the claim. Most types of investment business are covered for up to a total of £50,000. The Channel Island subsidiaries are not covered by the UK Financial Services Compensation Scheme; the offices of Royal Bank of Canada (Channel Islands) Limited in Guernsey and Jersey are covered by the respective compensation schemes in these jurisdictions for deposit taking business only.