Lately the market’s attention on the U.S.-China trade dispute has centered on rapidly evolving, sometimes contradictory events—from President Trump’s biting tweet about President Xi’s newfound status as an “enemy”; to the tariff increase on US$550B in Chinese goods; and then to Trump’s abrupt change in tone as he characterized the trade negotiations constructively.

China’s retorts have garnered attention as well, with the latest coming in the form of an olive branch. China will hold off on retaliating against Trump’s newly planned tariff hikes to “prevent escalation of the trade war.”

The exchanges left many questions unanswered as market participants searched for clues about whether a trade deal is feasible, and if so, when.

It’s important for investors to stay tuned into the bigger picture. There is much more to the story than this sparring match or the current state of negotiations. To us, the trade dispute is merely a symptom of a simmering geopolitical rivalry between the U.S. and China that has the potential to intensify over the long term.

Rather than an all-encompassing agreement, we think the best-case scenario is a cosmetic trade deal sometime before the 2020 U.S. presidential election—meaning, a deal that would initially generate some buzz and excitement but would prove to be light on substance in the end, similar to NAFTA 2.0.

Trade deal or not, we doubt the competition between the U.S. and China will let up.

Words matter

As the trade dispute has worn on, it has become clearer in government policy documents and statements by officials that the U.S. does not view China as a potential partner, but sees it as a competitor, at best, or a rival or enemy, depending on who is doing the talking.

A hawkish view on China is uniquely bipartisan and nonpartisan, as there are critics of the Middle Kingdom on each side of the political aisle and within key agencies.

A consequential shift occurred in early 2018, for example, when the Pentagon changed its nearly 20-year focus on terrorism as the greatest threat facing the country and instead put China and Russia atop the list.

The National Defense Strategy summary report stated, “China is a strategic competitor using predatory economics to intimidate its neighbors while militarizing features in the South China Sea.” It argued that China’s goal is “displacement of the United States to achieve global preeminence.”

Other assessments of China by U.S. government entities and elected officials are even more aggressive.

How does a country forge a comprehensive trade deal if it views its trading “partner” as a serious threat to its hegemony? When push comes to shove, we don’t think it would, even if Trump reverts back to calling Xi his “good friend.”

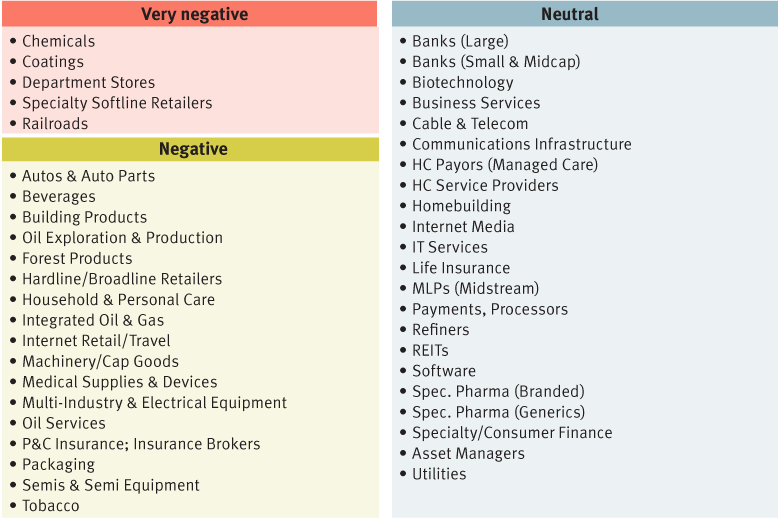

China trade war/tariff risk by industry

How RBC Capital Markets industry analysts assess the risk to demand for the U.S. stocks they cover

Note: Scale used in survey: +2 = very positive, +1 = positive, 0 = neutral, -1 = negative, -2 = very negative; no industries were viewed as positive or very positive in this question.

Source - RBC Capital Markets U.S. Equity Strategy, RBC Capital Markets estimates; table published in the August RBC Macroscope, survey from May 2019.

Full-court press

The other roadblock to a comprehensive deal is that, from China’s perspective, the Trump administration is asking for the moon. The U.S. seeks to change China’s development plans, economic structure, laws, regulations, and ideology.

It aims to thwart China’s long-term strategic economic programs, Made in China 2025 and the Belt and Road Initiative. The U.S. views these initiatives as security threats and expansions of China’s state-controlled industrial and technology policies.

The U.S. also wants China to further reform and reduce support for its state-owned enterprise (SOE) system—never mind that China has significantly curtailed this sector over the past 20 years. The Trump administration is asking China to tighten its intellectual property laws, stop so-called forced technology transfers, and relax barriers for joint ventures with foreign companies, among other requests.

Even though some of the U.S. demands have merit and could be addressed at least in part in a “cosmetic” trade deal, why would China give up the long-term strategic goals of Made in China 2025 and the Belt and Road Initiative? We don’t think it will, and this is another reason a groundbreaking, comprehensive trade agreement seems unlikely.

Get used to it

To us, the trade dispute is part of a broader geopolitical struggle between the U.S.-led unipolar framework that has existed since the end of the Cold War, and what China and other nations see as an inevitable shift toward a multipolar world order in which various powers exert authority.

The U.S.-China rivalry could play out over many years and drift on and off the market’s radar screen, sometimes impacting equity performance when trade, tariff, and economic growth issues surface. At other times, the rivalry will likely stay in the background, not driving equities in either direction, as is often the case with geopolitical struggles. Trade deal or not, we think the tensions between the two nations are something investors need to get used to.

Required disclosures

Research resources

RBC Wealth Management, a division of RBC Capital Markets, LLC, Member NYSE/FINRA/SIPC.