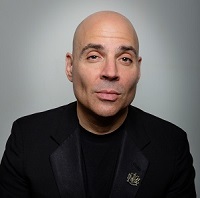

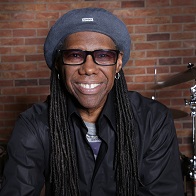

New players have sought to disrupt the existing business models, and redominant among these is Hipgnosis Songs Fund, a music IP investment and management company. Since going public in 2018, it has grown to a $2bn business. We caught up with CEO Merck Mercuriadis and legendary musician and songwriter Nile Rodgers at our virtual Media Forum.

What was the catalyst for change?

According to Mercuriadis, there were two factors that led to the genesis of Hipgnosis. “We felt the songwriter was delivering the most important component to an artist having a hit song, but was the lowest on the totem pole in terms of getting paid. We wanted to change that.”

Concurrent with that, streaming was finally starting to take hold. Technology had almost killed the music industry and had left songs at very attractive prices. Says Mercuriadis, “We knew that streaming was going blow the pie up all over again.”

Mercuriadis and Rodgers started ideating: songs were available at attractive prices, so they could acquire them and package them as an asset class. They could then go to institutional investors and demonstrate that proven songs had a reliable and economically uncorrelated income that could generate a good shareholder return.

They also felt they would do a better and more efficient job of actively managing the songs and collecting royalties. In Mercuriadis’ eyes, the traditional publishing model, where big companies focused on new IP rather than the classic songs, was broken. “The passive income from classic songs underwrites new IP but they’re allowed to languish. When you have 20,000 songs per person to manage, you’re not going out to create new opportunities for those songs. We could add huge value by putting that time and effort in.”

A shift in the industry

The second phase is to leverage the power of that asset class to end the disparity of where songwriters currently sit in the economic equation.

Rodgers explains from the perspective of a songwriter: “I got signed because I wrote the songs, but I had a more substantial income from live performances. We didn’t make a big deal of not getting fairly paid at the time because we loved being in the music business. Now the pandemic has really made it clear to a lot of artists that the house we built as songwriters is not being fair to us. Now is the time, as we can see the long-tail of hit songs, to make it more equitable.”

His experience underscores a shift in the industry. As Mercuriadis highlighted, from the post-Beatles era to 2010, 90% of artists wrote their own songs. Today, 90% of artists being signed are reliant on outside songwriters. There has not been a Billboard Top 100 Album of the Year since 2014 without an outside song writer. So the discrepancy is more visible where a top performer might earn $1m in a night performing, but the actual songwriter receives only small royalties.

Their model has been well received by songwriters. “These songs are like our children,” says Rodgers. “For writers to think of their music as a viable asset class that others want to invest in is an amazing matter of pride for them.” For the first time in years they’re seeing revenues from sources they’d not seen before, yet with the reassurance that they won’t just pursue every licensing deal.

Where will music publishing’s growth coming from?

In a streaming paradigm, Mercuriadis highlights that music has gone from being a luxury to a utility purchase. “Growing up in our business, we only dreamed about one thing: platinum records.” That equates to one million copies, which in the U.S., means a purchase by 1 in 360 people. He contrasts it with today’s world where 100 million U.S. homes are paying $10 a month for a premium music subscription. “We’ve gone from a model that was 1 in 360 to 1 in 4.”

Streaming has also ignited global emerging markets. Where there were previously illicit markets where people would pay $1 for a bootleg, now we have smartphones and streaming subscriptions, and Spotify recently opened in 60 other countries as streaming penetration rates are growing. “So for a musician like Rodgers who’d never received overseas royalties, now checks are rolling in from China to Senegal for the first time in 45 years,” notes Mercuriadis.

How to deliver greater equity in the music business

Their drive to create more equity in the industry also extends to race. “Black music has been making the world go round for 70 years,” observes Mercuriadis. Performers like Elvis, the Beatles and the Rolling Stones often made their names singing songs written by Black artists. But as Rodgers recounts, the inequity in music was a microcosm of wider society as he was signed on very different contract terms compared to his White contemporaries.

Fast forward to 2021 and it’s imperative says Mercuriadis, “that any company, judged in its actions, reflects the values of the people it makes money with and from.” His firm recently took action following the shooting of Ahmaud Arbery, penning an open letter to the Governor of Georgia calling for justice, and which was soon followed by action in the case.