The week-long gathering of government, business and civil society leaders, in Davos, Switzerland for the World Economic Forum, was designed to focus on a global crisis of trust. And yet on the Forum’s final day, the world’s leading stock markets — a good measure of trust — ended at record highs. At the same time, more humans than ever, in more countries than ever, are preparing to vote in democratic elections this year. Global trade, another measure of trust, is on the rise again, albeit slowly.

That’s Davos for you — one of the world’s most eclectic and energetic gatherings that is both a good window on the year ahead, and a place that gets as much wrong (social media, global financial crisis, Brexit and COVID) as it gets right. This year’s Forum, the 54th, attracted 3,000 delegates, including 350 government leaders and ministers, and 80 national security leaders. It also attracted tech executives, entrepreneurs, academics and social activists from around the world.

The overall mood? Economically tepid, politically sour, tech excited and security nervous. One Davos-goer called it “realistic optimism.” Another preferred “radical uncertainty,” which could foster a time of creative destruction, and remarkable progress — or just a time of destruction.

Here’s some of what I took away:

1. The economic mood is tepid

The Davos crowd seemed confident for modest economic growth this year and slowing inflation, which should allow central banks to cut interest rates — but not too much or too fast. Business leaders and economists largely called for a soft landing of the U.S. economy. Then again, that was the Davos mood a year ago — and the U.S. economy finished 2023 with GDP growth above 2.5%. A lack of recession, and persistent costs pressures, may prevent inflation from slowing much further or the U.S. Federal Reserve from moving more aggressively on rates. Among the inflationary forces: election-year spending in the U.S., trade disruptions like we’re seeing the Red Sea (war) and Panama Canal (climate), and skills shortages. Overall, North American and European consumers are in good shape financially; in fact, luxury spending is at all-time highs. There’s also plenty of capital flowing out of the oil-rich Persian Gulf, helping to push up asset prices. But the wild cards: Washington now spends 18% of its budget on debt servicing, which may force spending cuts, while China’s economic prospects are slumping and its real estate market sliding. Those two economies, which account for a third of global GDP, may present the biggest risks to growth, with the interest rate outlook holding the balance.

2. China is shrinking

In just five years, China has gone from WEF leader to WEF laggard. Premier Li Qiang tried to change that with his Davos debut, bringing a large delegation and taking the opening keynote slot to pitch the world on China’s resilience. There weren’t many takers. China saw large-scale outflows of foreign investment in the run-up to Davos, and finished the week with Shanghai losing its spot as Asia’s most valuable equity market to Tokyo. China’s population also shrank in 2023 for the second consecutive year. Birth rates are at record lows, and it’s now home to the largest number of senior citizens in the world. Li urged Washington to remove trade sanctions, reverse academic bans, and pull back from the technology restrictions that are scaring a lot of companies from doing business in China. The world recorded 5,400 trade actions in 2023, double what it was before the pandemic, with about 20% of them directed at China. Investment, meanwhile, has shifted materially to Vietnam, Indonesia, Mexico and India — including billions from Chinese companies. The message from the Americans and Europeans was clear: they’ll no longer rely on one country, or one region, for what they need.

3. America is rebalancing

The U.S. came to Davos as a lonely superpower that could go in one of two directions this year. The Biden administration sent its top foreign policy brains — Antony Blinken and Jake Sullivan — to stress, in Sullivan’s words, “we’re not turning inward.” They described the Biden doctrine as “variable geometry” changing by region, situation and timeframe. It’s a mix of ideals and interests, which Sullivan calls “strategic competition in an age of interdependence.” A world of frenemies, in other words. The Biden team suggested it will continue to box in rivals with sanctions, technology restrictions and military might, including strikes against their proxies. That seems to be well understood by America’s adversaries. Some of its friends also shared concerns about a possible Trump presidency and return to America First-ism. Europeans are worried Trump would ease up on Russia, and joined others in sharing concerns that Trump 2.0 would go hard at Europe, Canada and Mexico over trade. German Finance Minister Christian Lindner said Europe needs to strengthen its defences, technology capacity and economic independence — to meet whoever’s President next year from a position of strength. No matter the outcome in November, the prospects for global cooperation are limited.

4. Populism is rising

The theme of trust fostered plenty of conversations around democracy and what the world’s voters will be looking for in 2024. In a word: change. There are 50 scheduled elections this year, from Indonesia, India and Pakistan to the European Union, Britain and Mexico — and, of course, the U.S. There’s no single trend emerging other than, in many countries, a taste for change among a pandemic-scarred public. Argentina’s new libertarian president, Javier Milei, took centre stage to give a very anti-WEF speech about the power of unbridled capitalism and the “extortion” of taxes, signaling the kind of disruptive messaging that’s gaining ground. Milei may be an outlier — the Wall Street Journal called his speech “a spine transplant” — but the hunger for political and economic change is not. Only 16% of Americans trust their federal government “to do the right thing” — near a record low after the financial crisis and down from 20% in 2022. The historian Niall Ferguson compared the current mood to the Gilded Age of the 1920s, when populism on both the right and left found new footing as income inequalities rose. Some of it is also rooted in that meta-theme of trust, as the pandemic rattled many people’s confidence in institutions, and shaped an emerging generation that is less optimistic about the future.

5. AI is dividing

Artificial intelligence was the mega-meme of the week. Bill Gates set the tone, telling a Davos crowd he thinks AI will be bigger than the invention of the Internet. The ensuing debates questioned whether the Forum’s belief in creative destruction — let the market pick winners — is fit for a new tech age in which market concentration seems to be growing at warp speed. Much of the regulatory conversation focused on the power of the big three cloud providers (Amazon, Microsoft and Google) and their dominance with data, the rocket fuel of AI. “There’s no data like more data,” cautioned Erik Brynjolfsson, who heads the Stanford Digital Economy Lab. The International Monetary Fund also warned of growing economic disparities created by AI, between regions and between generations (although Microsoft’s Satya Nadella, who grew up in India, said he’s seen firsthand how technology can flatten the world.) Others stressed the perceived failure by governments to reign in social media in its early years. European leaders, in particular, stressed their intention to regulate AI, even if it slows innovation, while the U.S. and Britain are aiming for a more permissive approach, preferring to correct missteps than prevent steps. “No one knows the future but we have agency over the future,” said Jeremy Hunt, Britain’s Chancellor of the Exchequer. “We have choices.”

6. AI is accelerating

Davos’s main promenade was draped with banners proclaiming the positive power of AI, with plenty of stores converted to trade pavilions for the week to promote artificial intelligence. I attended a lunch in one of the shops, run by an American AI startup that wanted to hear from big companies — industrial manufacturing, health care and robotics, among them — about their experiences with AI. The conversation boiled down to one word: productivity. Most companies are using AI to boost the performance of sales forces, call centres and coding teams — and to cut employee time spent writing reports and producing decks, which AI is getting good at. Few employers at Davos, or surveyed for the many consulting firm reports released during the Forum, said they planned to cut jobs because of AI. Most said they’re looking instead to increase revenue. Accenture is aiming to equip most of its 740,000 global employees with AI tools, just as it did with other software tools. Albert Bouria, the CEO of Pfizer, predicted “a renaissance in life sciences” because of AI’s speed in exploring molecule sequences for drugs. To harness the creative power of AI, Sachin Dev Duggar, co-founder of Builder.ai, said the focus needs to shift from technology to organizational culture and learning. As he put it, “How do you put the superhero cape on every employee instead of them thinking AI is the superhero?”

7. AI is facing limits

If politicians at Davos worried about jobs and privacy, and business leaders focused on performance, some of the techies behind AI spoke a bit more about its limitations, warning the rhetoric is outpacing reality. Blame it on YouTube. Generative AI models like ChatGPT may be approaching limits, for now, because they are rooted in text-based learning — and they’ve consumed pretty much the entire universe of text. But no large language learning model has yet to conquer video, or been able to learn through trial-and-error, which is how humans do our greatest learning, as babies and infants. Yann LeCun, the head of AI at Meta, said a typical 4-year-old has absorbed 50 times more information than the biggest LLMs. Moreover, the human world’s information supply is growing more through video than text. Another scientist explained Generative AI is largely about association, not causality, and therefore has limits in terms of logic and judgment, not to mention sensitivity and foresight. “It’s why computers don’t have common sense,” he said. He compared it to airplanes and birds. Airplanes are faster but can’t do a fraction of the things birds can. What generative AI can do is help humans solve problems, especially ones that require finding subtle patterns in large homogenous data sets, like a drug sequence. Or climate patterns and their causes.

8. Climate is waning

It was hard not to notice the waning of climate as an issue at the Forum, amidst all the excitement around AI and anxiety over geopolitics. That’s not necessarily a bad thing. The focus of many climate sessions I attended — some with just a handful of people in the room — was on action, much more than angst or announcements. I attended one working breakfast, with energy, finance and industrial sector executives, who agreed this has to be the year of Final Investment Decisions, or FIDs, to get far more decarbonization projects off the ground (or in the ground). Among the barriers: a lack of global industrial carbon pricing, compliance costs, and a shortage of working models for blended finance between government, investors and banks. A sharper focus on a few breakthrough projects, with clear deadlines, might help. At a time of higher interest rates, better rates of return are also necessary, especially in renewable energy, which the world is aiming to triple by 2030. That won’t be easy as regulations and community resistance are already hampering growth. In the U.S., legal objections to solar and wind projects have grown six-fold. Some new approaches to governance may be needed if the world is to install massive new energy systems in half a decade. “Maybe climate change needs to be treated as urgently as war,” said economist Mariana Mazzucato.

9. Building is booming

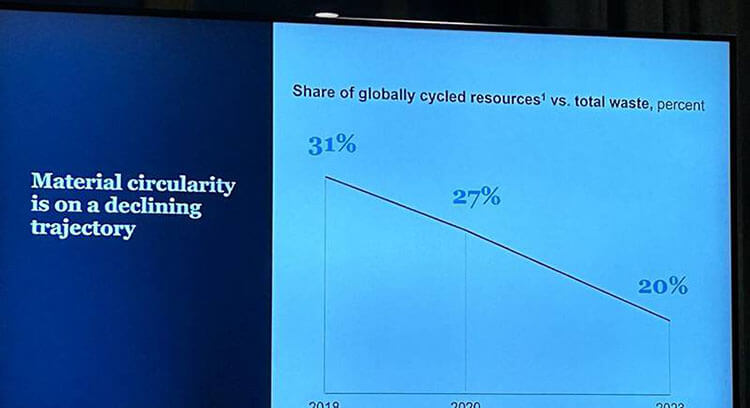

One of the reasons we’re falling behind our climate goals is we keep building as we have for ages. The world is on course to add the equivalent of China’s housing stock over the next 25 years, particularly in developing countries where millions are on the move to cities. India alone is adding the equivalent of another Chicago every year. The construction and operating of buildings accounts for 26% of the world’s emissions. We need to change heating and cooling systems, for starters. But we also need to transform the bricks, concrete, glass and steel that make up all those new buildings. Europe has led the way with recycled building materials— but that supply needs to double by 2030. Challenge is, even in Europe, every city seems to want its own building codes, which prevents suppliers from creating mass recycling plants. I attended a working session with planners and builders who said that challenges aside, they’re seeing in Europe recycling costs approach parity. Still, there’s no sign of recycling in developing countries where most of the world’s new structures will be built. “At the end of the day, everything has to be a financial play,” said Christian Ulbrich, the CEO of real estate giant JLL.

10. Agriculture is growing

In a region known for cow and sheep rearing, the Forum is finally starting to give agriculture its due. It’s promoting food systems on its agenda, and launched a “100 Million Farmers” initiative to advance sustainable agriculture. Agri-food systems account for 30% of global GHG emissions, 70% of freshwater use, and 80% of tropical deforestation — pressures that may grow in a world that’s projected to add 500 million more people by 2030. The Forum brought together governments, food companies and farmers to help solve that, largely by finding new ways to finance farmers for what they preserve as well as what they produce. I had the opportunity to write a piece for the Forum “3 ways to unlock the potential of climate-smart agriculture” that was part of the debate. I also spoke to a group of farmers and food producers from Mexico, Malaysia and the Philippines, and then joined a working session of agriculture ministers, farmers and agri-food CEOs to map out options. We agreed governments need to retool farm subsidies, which add up to $3 trillion a year, to reward sustainability and not just production. There’s another big opportunity for carbon credits to allow polluters to pay farmers for the emissions their land captures. Governments and universities also need to shift research and development spending to invest more in agriculture, which currently accounts for only 2% of the world’s R&D. Tanzania’s vice president Philip Mpango put it to our group: “We need to make agriculture sexy.”

For more, go to RBC Economics & Thought Leadership.

Download the Report