We have observed remarkable momentum across the sustainable finance market every year since the launch of the Sustainable Finance Group five years ago, and 2023 was no exception. In last year’s edition of this report, we anticipated that increasing sophistication of market participants and regulatory advancements would contribute to “a great reset” for ESG integration and sustainable finance. 2023 was indeed a year where we saw a leap forward in market maturity, and looking ahead to 2024, we consider three themes that reflect this continued progress: a focus on precision in terminology as the term ‘ESG’ enters its third decade of usage; pragmatic and credible solutions accelerating real-economy decarbonization; and a new era for sustainability-related disclosure as jurisdictions around the world contemplate a shift toward mandatory reporting.

Key Themes for 2024

- Language Matters: More Precision, More Clarity, More Impact

- Pragmatic and Credible Solutions Accelerate Real-Economy Decarbonization

- A New Era for Sustainability-Related Disclosure

Language Matters: More Precision, More Clarity, More Impact

‘ESG’ Turns 20

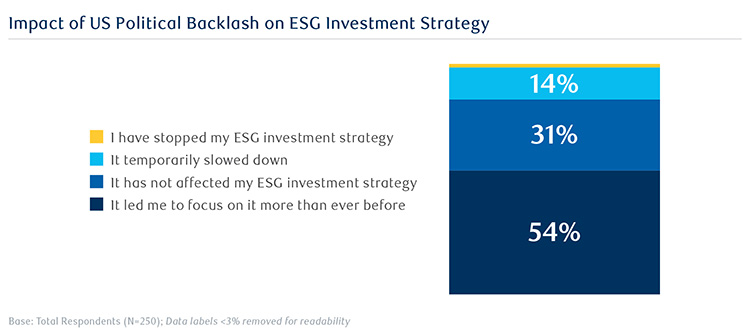

In 2024, the term ‘ESG’ will turn 20. The acronym, first used in a 2004 United Nations report titled Who Cares Wins, was originally coined to provide the financial sector with recommendations on how to better integrate environmental, social, and governance considerations that could have a material impact on the value of an investment.[1] In recent years, however, we have observed growing politicization of, and subsequent backlash against, the term ‘ESG’, particularly in the United States. While this backlash has attracted considerable media attention, it has not translated to meaningful behavioural change on the part of institutional investors. Indeed, a November 2023 Bloomberg report that surveyed 250 investors around the world revealed that the backlash has had the opposite effect: over half of the investors surveyed noted that US political backlash has led to focusing their attention on ESG integration more than ever before.[2]

Source: Bloomberg Intelligence ESG Strategy (November 2023)

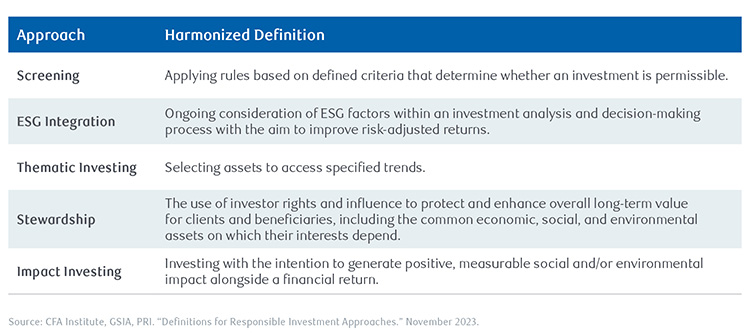

Much of this ‘ESG backlash’ stems from a fundamental lack of understanding or misrepresentation. The integration of financially material ESG considerations in investment decision-making is not aligned with a specific political ideology, nor should it be considered a “movement”. Rather, it is simply about understanding the full scope of data likely to be relevant in investment decision-making. Unfortunately, in recent years, the term ‘ESG’ has been increasingly conflated with other concepts – particularly screening and impact investing – which has distorted the term’s original meaning. In late 2023, three influential organizations – the CFA Institute, the Global Sustainable Investment Alliance (“GSIA”), and the Principles for Responsible Investment (“PRI”) – jointly published a report outlining a set of harmonized definitions to ensure consistency of understanding and usage across different responsible investment approaches and aligned on a shared definition of “ESG integration”.[3]

In December 2023, IOSCO published a report titled Supervisory Practices to Address Greenwashing which reiterated a previous call for action recommending that “market participants should consider coalescing around a set of globally consistent sustainability-related terms.”[4] The report noted that while some of the challenges associated with greenwashing are currently being addressed – for example, a growing number of jurisdictions have requirements in place that address sustainability-related disclosures at the product level for asset managers – greenwashing remains a fundamental market concern and other malpractices, such as greenhushing, are becoming increasingly prominent.[5] Greenhushing can be understood as “the act of corporate management teams under-reporting or hiding their sustainability credentials in order to evade investor scrutiny.”[6],[7] IOSCO notes that several jurisdictions have explicitly addressed this behavior, including the Australian Securities & Investments Commission, which recently warned entities against the practice of greenhushing and said that it represented a form of greenwashing.[8] The European Securities and Markets Authority has also noted that minimizing ESG commitments and achievements could be considered a case of omission of sustainability information, thereby undermining investors’ ability to access information relevant and material to investment decision-making. [9]

In 2024, as the term ‘ESG’ enters its third decade of usage, we anticipate that stakeholder expectations for high-quality and comprehensive sustainability disclosures, paired with corporate efforts to mitigate the risk of real or perceived greenwashing, will result in greater specificity in the language used to describe sustainability-related initiatives and impacts.

As the market continues to mature, we are hopeful that more precision and consistency in the language we use will help to remove ambiguity and return the focus to the original intention of ESG integration: understanding the factors that drive opportunity, risk, and value creation.

Regulation of Fund Names Globally

As the market for sustainable funds matures, regulators are responding to growing demand from market participants for clearer guidance related to the naming of funds with sustainability themes. In 2024, we anticipate regulation pertaining to fund labelling to become more quantitative and systematic in nature in order to continue advancing transparency, credibility, and confidence in the market. The EU is currently reviewing its Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (“SFDR”) regime, which first came into effect in March 2021. While the SFDR was designed for disclosure purposes, in practice the market is using ‘Article 8’ and ‘Article 9’ – originally intended to classify funds depending on their level of sustainability and identify the corresponding level of disclosure required – as marketing labels.[10] As the EU evaluates opportunities to bolster the SFDR regime, next steps could potentially include adding more specificity to the current definitions of Article 8 and Article 9 or replacing the terms with a dedicated product categorization scheme with more granular criteria, similar to the approach that the UK has taken.

In November 2023, the UK Financial Conduct Authority (“FCA”) published a Policy Statement focused on Sustainability Disclosure Requirements (“SDR”) and investment labels.[11] The Statement built on a Consultation Paper published in 2022 that proposed the SDR framework, including a labelling regime for sustainable investment products. Starting in 2024, the SDR will introduce a new voluntary labelling scheme while restricting the use of certain sustainability-related terms in product names, such as “sustainable” and “impact”. The four proposed product labels include “sustainable focus”, “sustainable improvers”, “sustainable impact”, and “sustainable mixed goals”. The SDR also features a minimum threshold for all labels, whereby 70% of a product’s assets must be invested in line with the sustainability objective.[12] In Australia, the Department of the Treasury has also announced its intention to commence work in 2024 on standardizing the use of sustainability terminology in investment product marketing by introducing a labelling scheme that sets out minimum standards for what qualifies for a prescribed sustainability label.[13] In the US last year, the Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) adopted amendments to the Investment Company Act “Names Rule” in an effort to strengthen existing disclosure requirements and prevent misleading investment fund names. One important change included widening the scope of funds that must adhere to the “80 percent investment policy”, which stipulates that 80% of a fund’s investments must be aligned to what is implied by the name of the fund, to include funds with names that reference a thematic focus on ESG factors.[14]

Pragmatic and Credible Solutions Accelerate Real-Economy Decarbonization

Transition Finance Gets Local and Pragmatic

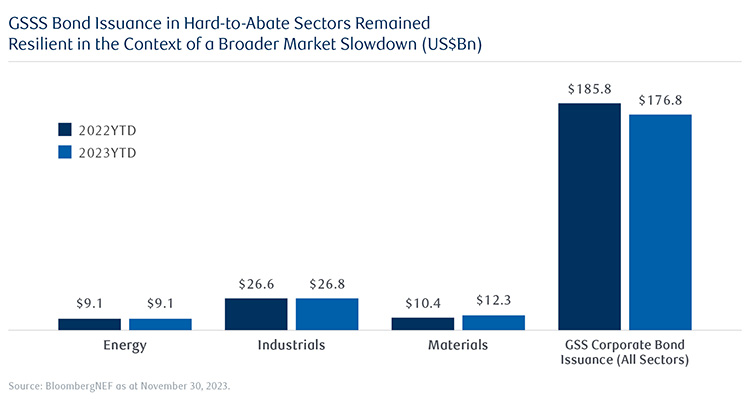

One of our key themes going into 2023 was “A Growing Market for Transition Finance”. As we noted last year, many of the most impactful opportunities for decarbonization and value creation can be found within the highest-emitting sectors. Despite a broader slowdown in the global sustainable debt market last year, 2023 saw an increase in issuers in hard-to-abate sectors integrating sustainable finance into their transition strategies. While overall green, social, and sustainability (GSS) bond issuance across all sectors decreased by 5% year-over-year, issuance in the Industrials and Materials sectors increased by 0.5% and 18%, respectively, while Energy sector issuance remained flat year-over-year.[15]

Source: BNEF (as of November 30, 2023)

While issuers in hard-to-abate sectors have typically gravitated toward sustainable debt labels with established market precedents, we see meaningful runway ahead for transition-labeled instruments. While transition bonds currently account for a small portion of the overall sustainable debt market, we have observed encouraging regional trends over the past year. A consensus between issuers and investors on what constitutes an eligible transition activity is a precursor to the growth of the transition label in the sustainable debt market, and countries that have articulated a clear decarbonization pathway are among those that are participating the most actively in the transition finance market. Japan, for example, which has published issuer-focused guidelines for climate transition finance, established sector-specific decarbonization roadmaps for a variety of hard-to-abate sectors, and recently published the world’s first sovereign transition finance framework, accounts for approximately 60% of total global transition bond issuance to date.[16] In 2024, the Japanese government is expected to issue the world’s first sovereign transition bond as part of the country’s broader plan to issue approximately 20 trillion yen (US$133Bn) worth of “green transition” bonds over the next decade to help finance efforts to achieve a net-zero economy, including the deployment of technologies such as hydrogen supply networks, carbon capture and utilization, synthetic fuels, and small nuclear reactors.[17],[18],[19]

We believe that transition finance will play a critical role in facilitating the shift to a net-zero economy by providing the capital required to support the transformation of emissions-intensive industries. In 2024, we expect this theme to remain top of mind, characterized by growing pragmatism and financial sector leadership. Transition taxonomies are currently under development around the world, including in Canada and Australia. In March 2023, Canada’s Sustainable Finance Action Council (“SFAC”) published its Taxonomy Roadmap Report which included suggested approaches to the categorization of green and transition activities in Canada. In Australia, the Australian Sustainable Finance Institute is building on the efforts of other jurisdictions, including the work of the Canadian SFAC, to develop a sustainable finance taxonomy that is internationally interoperable while reflective of the Australian economy and context.[20]

However, there is considerable uncertainty with respect to the timeframe for the development of transition taxonomies globally. In 2024, we anticipate that the absence of global or regional taxonomies for transition-related activities, paired with institutional investors eager to put capital to work, will result in the financial sector leading the way in defining its own approaches to transition finance. Investors are already building and applying bespoke approaches to developing their own transition taxonomies and investing in transition opportunities. We have observed some investors taking a “top-down” approach by identifying key sectors of focus or types of projects, while others take a sector-agnostic, or “bottom-up” approach, by developing proprietary internal taxonomies to identify transition opportunities based on an asset’s characteristics. While both approaches are designed to achieve the same result – channeling capital towards transition solutions – we expect investors to gravitate towards a bottom-up approach, recognizing that the transition of an asset in and of itself is an opportunity for value creation.

In a recent interview with RBC Capital Markets, Megan Starr, Partner and Global Head of Impact at The Carlyle Group, spoke to an evolution of how investors are approaching transition. In addition to green solutions, investors are recognizing the importance of decarbonizing the broader economy and engaging with high emitters.[21] Brookfield CEO Bruce Flatt echoed that perspective in an earlier interview with RBC CEO Dave McKay, noting that Brookfield bought a generating utility powered by coal and natural gas with the aim of transforming it into a renewables-powered business as a means of increasing value. As opportunities for transition-themed investing become increasingly evident, investors are recognizing the importance – and opportunities for value creation – associated with a pragmatic approach focused on the decarbonization of the high-emitting assets.[22]

Carbon Markets

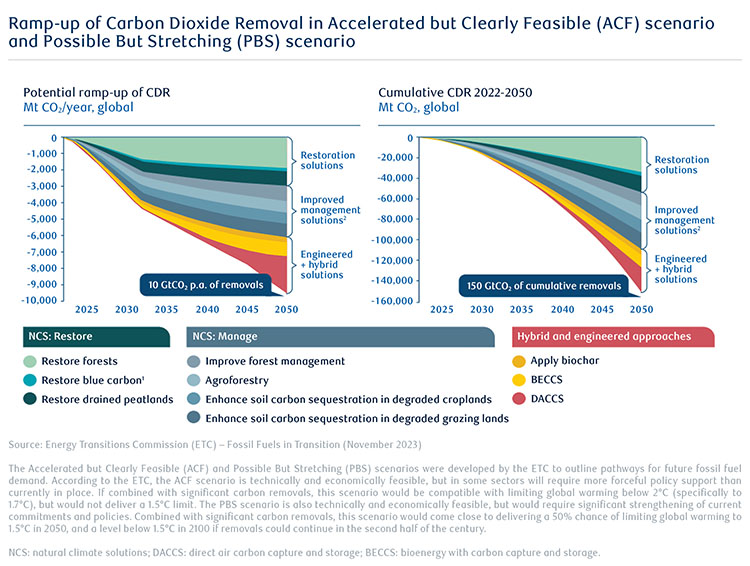

Just as transition finance will play a critical role in facilitating the shift to a net-zero economy, so too will the carbon markets. This is because even in the most aggressive net-zero scenarios there will be at least 7 billion tons of residual emissions from sectors with limited options to decarbonize that need to be addressed annually.[23] This will require vast amounts of carbon dioxide removal (“CDR”) which can come from both nature-based climate solutions (e.g., reforestation) and engineered or technology-based solutions (e.g., direct air capture). Scaling up CDR to meet this demand represents an enormous economic challenge and opportunity, requiring $130 billion in investment every year from now until 2050.[24] A scalable way to efficiently unlock private capital and create a business case for investment in CDR is through the carbon markets, meaning that they will be a crucial tool if the world is to reach net-zero.

As we recently wrote in our Key Takeaways from the Inaugural RBC Capital Markets Carbon Markets Conference, 2024 is shaping up to be a pivotal year for the carbon markets. While expected progress at COP28 on Article 6 (the proposed UN-administered global carbon market) stalled, there were still some significant positive developments for voluntary carbon markets (“VCM”) including a new “Integrity Coalition” formed by the six main VCM registries and supported by a new end-to-end high integrity framework developed by the Science Based Targets Initiative, GHG Protocol, and Integrity Council for Voluntary Carbon Markets (“ICVCM”), among others. While compliance markets continue their steady growth, 2024 will be a pivotal year for the VCM and its future success will depend on the uptake and outcomes of the various initiatives focused on enhancing credibility and regulation such as the aforementioned ICVCM and Integrity Coalition. We often say that there is never a dull day in the carbon markets, and we expect that 2024 will prove to be no exception.

A New Era for Sustainability-Related Disclosure

Jurisdictional Adoption of the ISSB Standards

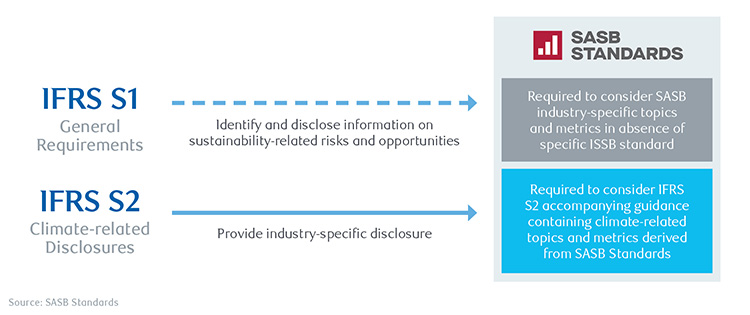

In 2024, we anticipate regulatory momentum to increase with regards to the adoption of mandatory sustainability-related disclosures. The finalization in June 2023 of the International Sustainability Standards Board’s (“ISSB”) inaugural set of sustainability disclosure standards, IFRS S1 and IFRS S2 (“the ISSB Standards”), represented a major developmental milestone for the global sustainable finance market by consolidating the previous work of investor-focused reporting initiatives, including the industry-specific Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (“SASB”) Standards.[25] The ISSB Standards come into effect for reporting periods beginning on or after January 1, 2024, which means that we can expect to see the first reports aligned with the ISSB Standards published in 2025.

In July 2023, the International Organization of Securities Commissions (“IOSCO”) endorsed the ISSB Standards and called on its member jurisdictions, which collectively regulate over 95% of the world’s financial markets, to consider ways in which they might adopt or apply the ISSB Standards.[26] The UK has indicated its intention to publish UK Sustainability Disclosure Standards, based on IFRS S1 and S2, in July 2024, and dozens of other jurisdictions are actively considering pathways toward mandatory application of the ISSB Standards.[27],[28]

As countries around the world contemplate the integration of the ISSB Standards in regulatory frameworks, we will be watching two dynamics unfold in the year ahead: first, interoperability between the ISSB Standards and other sustainability disclosure regimes; and second, the ways in which certain countries may build on the ISSB Standards to ensure that they are fit-for-purpose in different jurisdictional contexts.

The ISSB Standards: IFRS S1 and IFRS S2

Like the ISSB Standards, the EU Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (“CSRD”) comes into effect for reporting on fiscal years beginning on or after January 1, 2024. However, unlike the ISSB Standards, which remain voluntary until a jurisdiction decides otherwise, the CSRD requires in-scope companies operating within the EU to publish sustainability disclosures. Once fully implemented, the CSRD will require more than 50,000 companies operating within the EU to disclose sustainability information in line with the new European Sustainability Reporting Standards (“ESRS”), which are intended to be interoperable with the ISSB Standards. Many companies headquartered outside of the EU will also be affected as the CSRD is phased in; recent analysis conducted by the London Stock Exchange Group suggests that at least 10,000 non-EU companies will fall within the CSRD’s scope.[29],[30]

Interoperability and Regional ‘Building Blocks’

The concept of “double materiality” is an important point of distinction between the ESRS and the ISSB Standards and one that we believe will come into focus in 2024. While the ISSB Standards guide companies to disclose sustainability-related risks and opportunities through the lens of financial materiality – the sustainability factors that are likely to affect a company’s financial position – the CSRD requires companies to also disclose through the lens of “impact materiality”, defined as the impacts of a company’s operations and value chain on people or the environment.[31] Considering financial and impact materiality together yields a “double materiality” lens, and given the reach of the CSRD, we expect to see a growing number of multinational companies begin to incorporate the concept of double materiality in their disclosures in 2024.

An important related point is the way in which some jurisdictions expect to use the ISSB Standards as “building blocks” on which to add requirements to address regional-specific considerations. In Canada, for example, the Canadian Sustainability Standards Board (“CSSB”) is working with the ISSB to support the uptake of the ISSB Standards in Canada and highlight key issues for the Canadian context.[32] One key area where the CSSB expects to play a leading role is in the context of the inclusion of Indigenous voices. As part of its mandate, the CSSB will consider the need for any augmentation to the ISSB Standards and intends to conduct a consultation with Canadians over the coming months.[33]

In the US, the SEC’s final climate disclosure rule is anticipated in April 2024, and in the time elapsed since the rule was originally proposed in 2022, more stringent climate disclosure requirements have emerged, both globally and at the state level within the US.[34],[35] The CSRD is one example of this dynamic, but perhaps more notable are the two landmark bills enacted by the State of California in 2023 that would require certain companies that do business in the state to disclose Scope 1, 2, and 3 greenhouse gas (“GHG”) emissions starting in 2026.[36] As the architecture of mandatory sustainability-related disclosure falls into place around the world, the interoperability of different regimes is an important dynamic that we will be following closely in the year ahead.

Rising Focus on Supply Chain Transparency and Social Risks

As investors seek more information about risks and opportunities embedded in supply chains, and consumers seek to understand in greater detail the footprints and lifecycles associated with the products they purchase, we anticipate that disclosure expectations pertaining to the supply chain – particularly with regards to Scope 3 GHG emissions, responsible sourcing of critical metals, biodiversity and land use, and working conditions – will continue to heighten in 2024. A growing focus on accurate data collection, tracking, and performance measurement will require companies to invest in new tools and establish deeper engagement with partners throughout the supply chain. In addition to heightened expectations for supply chain transparency, we anticipate a rising focus on risks related to social inequality. In 2023, a new global taskforce was created to combine the efforts of the Taskforce on Inequality-related Financial Disclosures and the Taskforce on Social-related Financial Disclosures into a single initiative. The Taskforce on Inequality and Social-related Financial Disclosures (“TISFD”), described as the “TCFD for social risks”, is a multi-stakeholder initiative that includes the United Nations Development Program and the World Business Council for Sustainable Development, among others, and is expected to formally launch in the first half of 2024.[37],[38] The establishment and launch of the TISFD represents an important step toward developing a global framework for financial disclosures that encompass financially material social- and inequality-related risks and opportunities.

Looking ahead to 2024, we are encouraged to see interest from jurisdictions around the world with regards to the adoption of sustainability-related disclosure standards. At the same time, we also recognize the challenges that lie ahead from an implementation perspective. There is a meaningful amount of underlying infrastructure – systems, processes, and controls – that will be needed to support the integration of sustainability and financial reporting. During a review of recent stakeholder feedback at the ISSB’s December 2023 board meeting, the importance of capacity-building efforts to help support the implementation of the ISSB Standards emerged as a top priority.[39] Another important implementation consideration is the availability and quality of certain kinds of data. As corporates work toward making sustainability reporting assurance-ready, some types of information, especially pertaining to the value chain, may be initially limited. We anticipate that sustainability data from a corporate’s own operations to be assurance-ready at an earlier stage, while supply chain information gathered from partners will likely take more time.

Closing Thoughts: What’s Next for Sustainable Finance?

It is clear that ESG considerations are evolving, maturing, and more relevant than ever. The themes outlined in this year’s report – momentum toward more precision in the language we use when we talk about sustainable finance, a focus on sensible solutions to accelerate real-economy decarbonization, and jurisdictional adoption of sustainability-related disclosure requirements – will serve to further advance transparency and credibility across the market. Looking ahead, we see significant opportunities for the sustainable finance market to continue to support our corporate, institutional, and government clients as they set and achieve ambitious sustainability objectives. RBC Capital Markets provides sophisticated sustainable finance and ESG advisory solutions for our clients, and we look forward to continued partnership in 2024 to help advance the transition to a low-carbon economy and to a more equitable and inclusive society.

[1] 04-37665.global.compact_final (unepfi.org)

[2] Bloomberg Intelligence (BI) ESG Strategy. “BI ESG Market Navigator: A Global Dual Survey of C-Suite Executives and Senior Investors.” November 2023.

[3] https://rpc.cfainstitute.org/-/media/documents/article/industry-research/definitions-for-responsible-investment-approaches.pdf

[4] https://www.iosco.org/library/pubdocs/pdf/IOSCOPD750.pdf

[5] https://www.iosco.org/library/pubdocs/pdf/IOSCOPD750.pdf

[6] https://planet-tracker.org/greenhushing-sophisticated-greenwashing/

[7] https://www.esma.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2023-01/esma22-106-4384_smsg_advice_on_greenwashing.pdf

[8] https://www.iosco.org/library/pubdocs/pdf/IOSCOPD750.pdf

[9] https://www.iosco.org/library/pubdocs/pdf/IOSCOPD750.pdf

[10] https://www.esma.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2023-05/ESMA30-1668416927-2473_Natasha_Cazenave_speech_AFME_2nd_Annual_Sustainable_Finance_Conference.pdf

[11] https://www.fca.org.uk/publication/policy/ps23-16.pdf

[12] Final Rules on UK Sustainability Disclosure Requirements and Investment Labels - Key Takeaways for Asset Managers | Insights | Sidley Austin LLP

[13] https://treasury.gov.au/consultation/c2023-456756

[14] https://www.sec.gov/news/press-release/2023-188

[15] Bloomberg; Data as at November 30, 2023

[16] Bloomberg New Energy Finance (BNEF), December 2023.

[17] https://www.mof.go.jp/english/policy/jgbs/publication/newsletter/jgb2023_11e.pdf

[18] https://asia.nikkei.com/Spotlight/Market-Spotlight/Japan-s-green-transition-bonds-find-more-open-minded-investors

[19] https://www.reuters.com/markets/rates-bonds/japan-issue-11-bln-climate-transition-bonds-february-sources-2023-12-05/

[20] https://www.asfi.org.au/taxonomy#:~:text=Learn%20more-,Taxonomy%20Development%20Phase,an%20Australian%20sustainable%20finance%20taxonomy.

[21] https://www.rbccm.com/en/story/story.page?dcr=templatedata/article/story/data/2023/08/more-better-faster

[22] https://www.rbccm.com/en/insights/story.page?dcr=templatedata/article/insights/data/2023/03/brookfield_is_powering_the_transition_to_net_zero

[23] Buck, H.J., Carton, W., Lund, J.F. et al. Why residual emissions matter right now. Nature Climate Change. 13, 351–358 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-022-01592-2; IPCC AR6 - Limited or No Overshoot 1.5°C Pathway. The projected range of residual emissions is 6.79 GtCO2e to 11.87 GtCO2e.

[24] McKinsey & Company: Global Energy Perspective 2022 "Achieved Commitments Scenario"

[25] By consolidating the previous work of market-led investor-focused reporting initiatives, including the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (“SASB”) Standards and the Task Force for Climate-related Financial Disclosures (“TCFD”) Recommendations, the ISSB Standards were designed to help companies disclose sustainability-related information to investors in a way that is consistent, comparable, and decision-useful.

[26] https://www.iosco.org/news/pdf/IOSCONEWS703.pdf

[27] UK Sustainability Disclosure Standards - GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

[28] IFRS - ISSB: Frequently Asked Questions

[29] https://www.wsj.com/articles/at-least-10-000-foreign-companies-to-be-hit-by-eu-sustainability-rules-307a1406

[30] https://www.esgtoday.com/sec-chair-warns-lack-of-climate-rule-exposes-thousands-of-u-s-companies-to-eu-climate-reporting-requirements/#:~:text=The%20SEC%20released%20its%20proposed,in%20some%20cases%20emissions%20emanating

[31] 06-02 Materiality Assessment SRB 230823 (efrag.org)

[32] Canadian Sustainability Standards Board (frascanada.ca)

[33] https://www.frascanada.ca/en/cssb/about/faqs

[4] https://news.bloomberglaw.com/business-and-practice/sec-goalposts-on-climate-disclosure-regulation-slide-into-2024

[35] https://www.reginfo.gov/public/do/eAgendaViewRule?pubId=202310&RIN=3235-AM87

[36] California enacts major climate-related disclosure laws (harvard.edu)

[37] https://thetifd.org/joint-statement-on-convergence-between-tifd-and-tsfd

[38] https://www.responsible-investor.com/groups-exploring-social-and-inequality-tcfd-equivalents-complete-merger/

[39] https://www.ifrs.org/content/dam/ifrs/meetings/2023/december/issb/ap2-feedback-summary-users-of-general-purpose-financial-reporting.pdf