Published June 27, 2022 | 3 min read

Key Points

- Pilot projects have already shown that vehicle-to-grid (V2G) could be a viable distributed energy source in the future.

- V2G holds promising benefits for utilities, consumers and regulators.

- A key hurdle to commercialization lies in restrictive battery warranties, which stop their use in V2G projects.

- In the future, we see utilities working more closely with the automakers, EV supply equipment manufacturers, and EV operators to help share risk and reduce capital needs.

The idea of electric vehicles (EVs) putting power back onto the grid has been underway since 2011, when Nissan and Mitsubishi deployed EVs as temporary home generators to aid earthquake relief efforts in Fukushima, Japan.

In the future, vehicle-to-grid (V2G) could serve more needs than just temporary power, with pilot projects from operators such as Nuvve, EVGo and ChargePoint already showing that V2G is feasible. Utilities are catching up with their own pilots, as EV ownership accelerates, but commercialization is likely as much as a decade away. However, in the US, V2G could experience a surge in interest under the recent federal target to achieve 50% new sales in EVs by 2030 and potential EV subsidies under the Biden administration’s Build Back Better plan.

The case for V2G

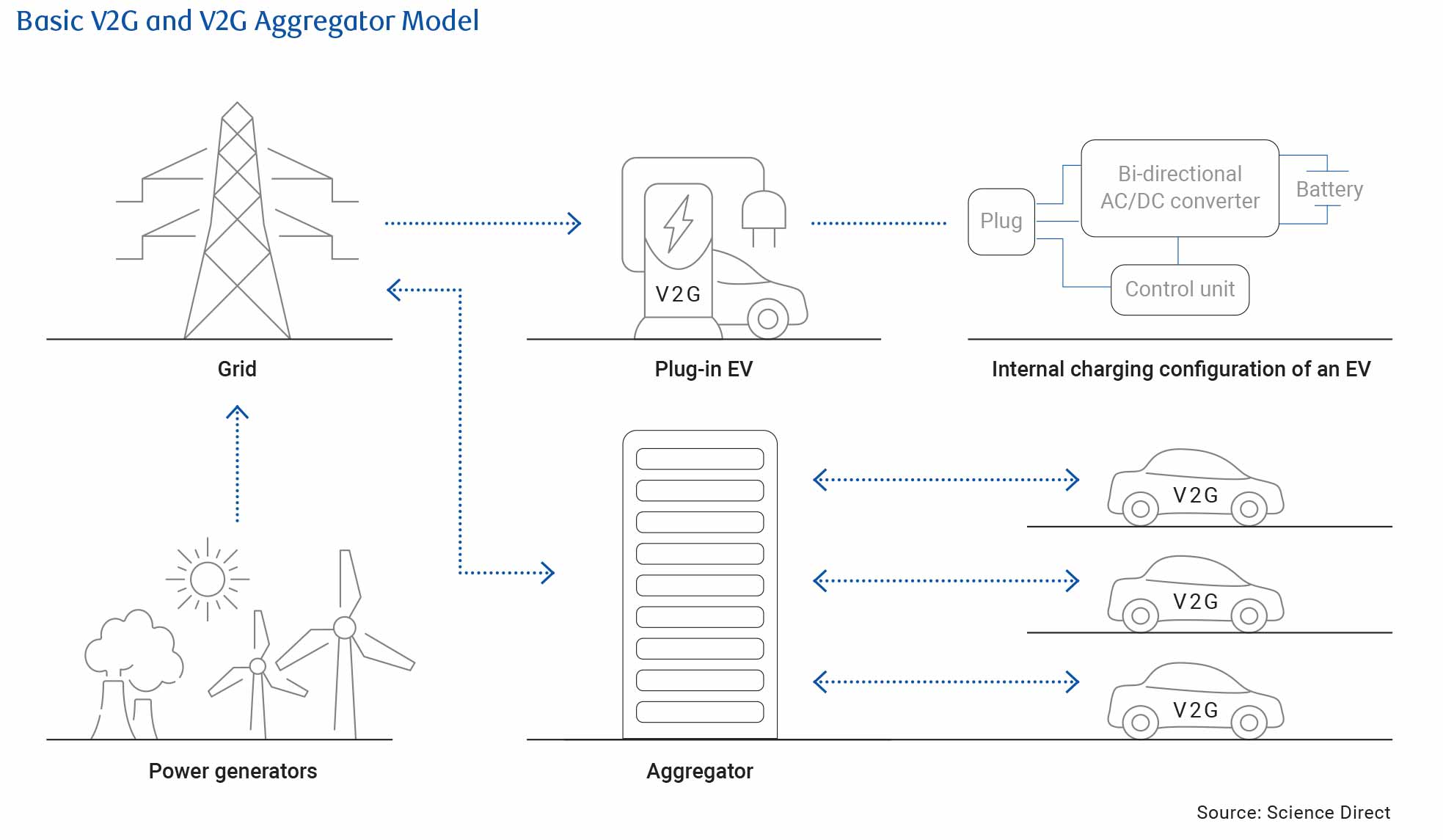

Utilities typically achieve decarbonization in several ways: shedding thermal generation, controlling emissions, building renewable assets, and demand resource management. V2G potentially checks all four options. Like stationary storage, V2G could be an effective way of storing excess green energy. One key difference is that capital needs to enable V2G are typically shared among the EV owner, the automaker, the EV supply equipment manufacturer, and utilities. While the relative dynamics among these parties can vary, there is clearly a smaller burden for utilities.

“For utilities, the benefits are clear. Utilities themselves may even become distributed energy resource (DER) aggregators. Consumers also stand to gain as they transition to prosumers, benefiting from lower cost of ownership for the EVs and reduced electric rates for grid users. Regulators will also likely be receptive to any innovation that keeps customer bills low. But can V2G be a meaningful contributor to the power grid?”

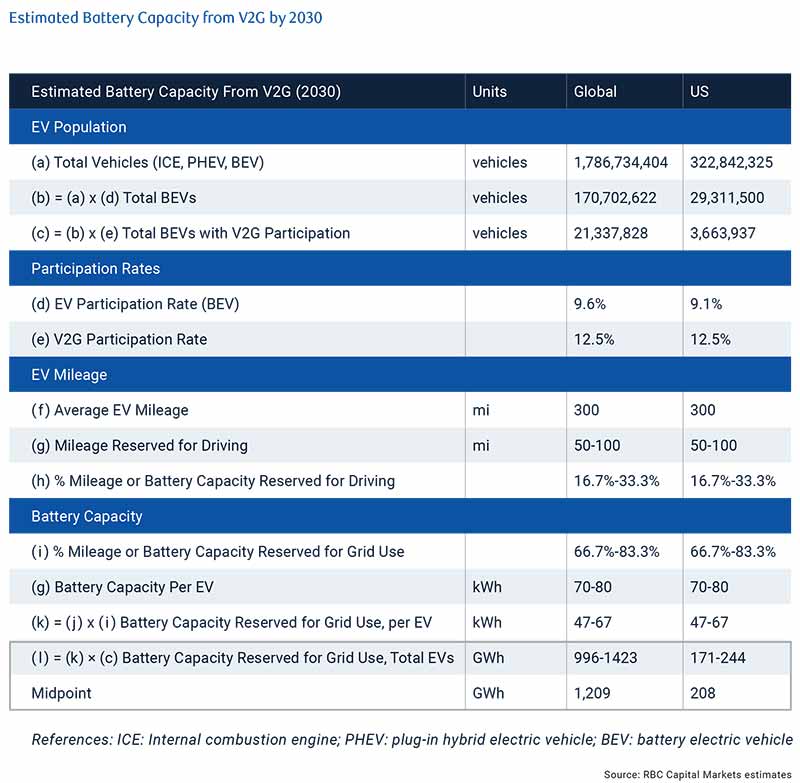

In terms of sheer battery capacity, mobile energy storage from V2G could surpass stationary storage by 2030. There are two factors that could support higher contributions from mobile energy storage: 1) higher EV capacities as consumers look for longer vehicle range capabilities, and 2) higher V2G adoption rates from membership programs that encourage consumers to commit to grid connection in exchange for discounts on their car. Should EV participation rate increase by 100-bps, we anticipate the midpoint of battery capacity reserved for grid use by 2030 to increase to 1336 GWh globally and 230 GWh domestically.

Accelerating adoption of V2G

Recent legislative focus on EV sales, charging infrastructure and battery cell production will encourage faster EV adoption, but it’s not just ownership of the cars that will power this change. While industry players agree that technology may not be the main hurdle, they recognize that V2G adoption is held back by reliability concerns, restrictive battery warranties, and industry standards under development. As a result, commercialization may still be several years away.

At the moment, battery warranties tend to disallow grid usage, as V2G could subject the batteries to unusual operating conditions.

“Automakers will need to get on board with producing batteries that are for use in V2G, or even choose to become operators of V2G themselves. The shift to different battery chemistries and emerging interoperable standards for EVs and charging stations will also help mass commercialization.”

The road ahead

We believe utilities will target commercial fleets for early V2G programs. These vehicles have larger battery capacities, achieve scale, and experience higher idling times during certain seasons. But regulated programs including bill management and retail rate reforms will entice private vehicle owners. VGI found that cases with the greatest benefits typically involve utilizing time-of-use (ToU) rates, demand charge reductions, and offpeak charging. Other use cases include standardizing EV rates, deploying smart meter infrastructure, and allowing V2G systems to qualify for state incentives.

V2G opens new behind-the-meter opportunities for utilities to electrify the grid. In the future, we see utilities working more closely with the automakers, EV supply equipment manufacturers, and EV operators to help share risk and reduce capital needs. The ways in which utilities choose to participate will vary (e.g., regulated vs. unregulated, owner operator vs. investor), but a trend toward decentralized energy seems clear.

Shelby Tucker and Joseph Spak authored “Some Say That Cars are for Driving – All We Know is That They Can Power the Grid,” published on December 2, 2021. For more information about the full report, please contact your RBC representative.