Below are excerpts from an article originally published on Barrons.com.

It has been decades since energy took on such a central role in global affairs. Oil and gas stocks soared last year as the war in Ukraine upended the market. Now, commodity prices are tumbling again, the stocks are wobbling, and an even bigger change—a global transition to clean energy—appears to be around the corner.

To understand how all these dynamics will play out in the coming years, Barron’s convened a roundtable of energy experts that met May 9 on Zoom.

The group included Helima Croft, head of global commodity strategy and Middle East and North Africa research at RBC Capital Markets; Dan Pickering, founder and chief investment officer at Pickering Energy Partners; Christyan Malek, global head of energy strategy and head of Europe, the Middle East, and Africa oil and gas equity research at J.P. Morgan; and Karim Fawaz, director of financial and capital markets at S&P Global Commodity Insights.

An edited version of the conversation follows.

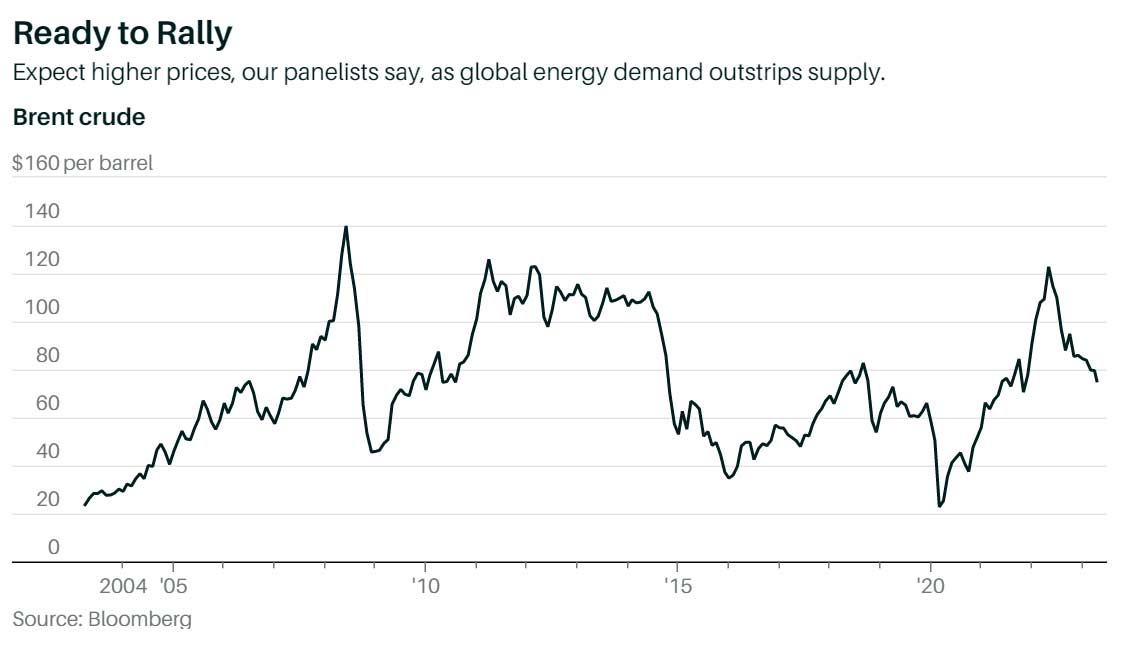

Barron’s: Everything seemed lined up for oil prices to rise after OPEC said last month that it would cut production. Yet, Brent crude, the global benchmark, is still $75 a barrel, and could be heading lower. Let’s begin with your oil-price targets for the end of 2023.

Karim Fawaz: A lot of people thought we had escaped the macro headwinds back in April, when OPEC [the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries] initiated voluntary production cuts. Clearly, that hasn’t been the case so far. There is still a lot of macro pressure. It is difficult to predict what will happen next month at the OPEC meeting, but we still see sequential demand growth between now and August of around three million barrels a day.

At the same time, you’re going to see another million barrels a day of supply come off the market because of OPEC production suspensions as the cuts go into effect. It’s very difficult to see a path where energy-market fundamentals don’t tighten significantly in the next two quarters, so we remain relatively constructive on prices. We still see Brent prices averaging $92 a barrel in the third quarter, and easing slightly into the end of the year to the mid- to high-$80s.

Dan, what is your price target for crude?

Dan Pickering: Forecasting is notoriously difficult, but to start with the long term, I’m pretty bullish on the next three to five years. I’ve got an $80 number for West Texas Intermediate [the U.S. benchmark for oil] as an average over that period. I expect things to improve over the remainder of this year, so $75 to $85 WTI at year end is my near-term target. Supply is constrained but demand is the wild card. The market is treating oil as a risk-off or risk-on asset. We should expect volatility, and I’m 100% convinced I’ll be wrong on that year-end price number.

Helima, what are your thoughts?

Helima Croft: I echo a lot of what was said. Oil really struggled with this sort of sum-of-all-fears worry. OPEC has shown that they are willing to midwife a recovery. It looks like they’re meeting in person in June, which seems a signal that they are willing to do more. There are also other geopolitical factors that continue to be important in the market, but might not be priced in. We still have a pipeline offline in Iraq, with no signs of an imminent restart. The Iran issue remains pretty important for the back half of the year. Right now, oil struggles when everyone focuses on the broader macroeconomic story. The fundamentals should come into the driver’s seat at some point in the back half of the year.

So, do you see prices moving higher or lower?

Croft: They could go lower because of macro concerns. But we see a path toward a $90 price environment, based on the fundamentals. And again, there are some wild cards out there on the geopolitical side that aren’t even factored in when we talk about $90.

Christyan, let’s hear from you.

Christyan Malek: We were bearish from 2013 to 2020. We turned formally bullish on the long term in our supercycle thesis in the spring of 2020, which was a difficult time, for obvious reasons. [A commodity supercycle is a period of sustained expansion, usually characterized by high prices.] Having said that, we have put the supercycle thesis on hold this year, and tend to think that this year is a bit of a write-off for energy. We turned bearish on energy in December of last year, both on the asset class and the commodities. It will be a difficult first half of the year. The rest of the year is highly dependent on the recession outlook. I expect that energy prices will be rangebound through the end of the year. Demand is like a sword hanging over the market.

By rangebound, do you mean Brent will stay in the high-$70s?

Malek: Yes. We have talked about the worst-case scenario being around $60 a barrel this year. OPEC stepped in to protect $60 oil, not $80 [as some other analysts have said]. We can expect more OPEC intervention. In other words, they’re not trying to create a higher-price scenario, but protect a really bad scenario from playing out. It’s not about trying to stoke the price at the expense of the consumer. If anything, it is protecting investment today to protect the consumer in years to come. Without that investment today, we could see severe energy inflation in the future. We have talked about $200 oil by 2025 as an upside scenario, with $80 being a long-run forecast for Brent.

We are less than a month from another OPEC meeting. OPEC is now in an alliance with Russia, with serious geopolitical implications. Helima, what do you expect to happen?

Croft: It’s really about market management. One of the key drivers for Saudi Arabia is to deliver on Vision 2030, its massive infrastructure and job-creation program. It grounds a lot of the country’s oil policy. The White House didn’t see an OPEC cut coming in October. Because it happened right before the midterm election, everything was seen through the prism of Washington politics, when in fact the Saudis were really trying to put in a circuit breaker to stop oil from falling quickly. I don’t see that the Saudis are going to end their relationship with Russia in terms of market management. If oil is in its current price range or potentially even lower at the OPEC meeting next month, then OPEC is prepared to take additional action. They believe they have to support the market until more fundamental factors reassert themselves.

Speaking of Russia, it has been more than a year since the invasion of Ukraine, and the war is still going on. Russian oil is still on the market; it’s just moving in different directions. What does this mean for oil and natural gas longer term?

Croft: The Biden administration was clear from the start of the war: It was going to sanction everything, but wanted to keep Russian energy flowing. It was deeply concerned about maintaining popular support for the war in an energy crisis. Primarily, the goal of price caps on Russian oil was to blunt the impact of the European Union’s package of sanctions, particularly the ban on oil services to move Russian barrels to third-party markets. That Russian oil is still going in large quantities to India and China was the key objective of price caps.

The Russians themselves decided to take their natural gas off the market. The question is: Has Europe built sufficient supply to get through winter? There is a lot of optimism in EU countries that they have built sufficient stockpiles to get through next winter, and the focus now is on 2024. But the real question is: Has Russia played its last card? Could we potentially see [energy] infrastructure attackslinked to Russia?

What do you think, Karim?

Fawaz: I mostly agree with Helima. The U.S. administration’s objective coming into the fall was fairly clear. It was safeguarding oil flows in a way that was destructive to Russian revenue. That has happened, to a large extent, partly because prices have been low enough that the majority of oil exports from Russia have been de facto trading below the price cap. A large share of Russia’s fleet has been able to access Western services. What’s more interesting to think about is, if prices move higher in the second half of the year, as we expect, and oil suddenly starts to trade near or above the price cap, will the EU start looking to enforce it more stringently?

The commodity that has been inspiring the most debate lately is natural gas, which soared to $9 per million British thermal units last year and crashed to $2 this year. Meanwhile, gas-related stocks haven’t fallen as much as the commodity. We’re in a relatively lengthy period with a lot of supply and, at least in the U.S., not a ton of export capacity for liquefied natural gas to sell that supply elsewhere. Where do prices for natural gas and the stocks go next, Dan?

Pickering: The siren call of new LNG export capacity in 2025 and 2026 is keeping the market pretty bullish on gas. A couple of LNG projects are coming online in 2025 and ’26, so U.S. producers will be able to export more of their product overseas. Despite low prices, you’re seeing a reluctance by the industry to slow productionactivity because no one wants to be behind the curve when the market, in theory, tightens up in late 2025. We’re in a Catch-22; the long term is bullish, the short term is bearish. Winter is always a wild card, but no one is expecting much out of natural-gas pricing in the near term. The risk is if LNG exports slip or new projects take longer to build. Then gas will have another leg down in sentiment.

Are you cautious on the stocks of gas-focused producers?

Pickering: The stocks have fallen. Antero Resources [ticker: AR] has been cut in half. It is starting to look interesting. The question is: What’s the catalyst for the stock to work, particularly relative to the oil names? Gas is sort of a no man’s land from a stock perspective. The stocks aren’t particularly expensive. The companies have their balance sheets in order. There isn’t financial distress. I’d rather play oil than gas from a stock market perspective, both the commodity and the companies that produce it. Really, these are 2025 stories, which means you probably get paid next year, not this year.

Christyan, you have written that the world isn’t investing enough in energy. But there seems to be plenty of natural gas.

Malek: There is so much additional gas coming online in the next few years. We see a race to the downside in gas. If anything, gas feels like it’s on a downward trend with fake highs because so much additional supply is coming online. China is switching a lot of its usage into coal, with less regard for net-zero emissions than it used to have. The extra production coming through in 2025 and ’26, whether from Qatar, the U.S., or potentially the Saudis, means having too much gas supply just when demand isn’t keeping up.

The reverse is true for oil. Remember the airports last year? You had a 10-minute queue just to get a coffee in Terminal 2 at Heathrow. That was because of very strong travel demand. Oil also carried a risk premium, too, which was a function of the concern around a lack of supply coming from Russia, which ultimately didn’t play out. OPEC had to add production to deal with the increase in demand, but also that risk premium. Now we’re seeing a mean reversion, or a correction in terms of how much production we need from OPEC to normalize demand. That is true in the West as we move past a partial lockdown and into a potential recession, and in China as we get past lockdown into whatever things look like after COVID.

Just what are you expecting?

Malek: Over the next 12 to 18 months, we’re going to progress through this choppy demand outlook as we find our feet, post-COVID. Demand has been [a more important issue than supply this year]. We’ll see it switch. In other words, supply becomes king. Demand doesn’t have to grow by multimillions of barrels a day every year. What we see in our numbers is supply growth grinding to a halt in 2024 and 2025, predominantly because shale is becoming the marginal-cost producer.

Come two or three years, shale productivity is going to plateau. We don’t have another [oil] basin as we did in Angola in the early 2000s. We don’t see any incremental quantity of supply past 2024. So how do we solve the deficit? We solve it through the price moving to a point where it starts to hurt demand. At that point, clearly, it’s whatever price OPEC is comfortable with.

How high, then, could the oil price go?

Malek: At J.P. Morgan, we believe the world can cope with $150 a barrel. There is plenty of scope to go up without hurting demand. It’s very different from any previous cycle. You have ESG [environmental, social, and corporate governance] pressures not to invest in oil. It comes at a higher [cost of capital] than it traditionally has. You have policy that’s conducive to clean energy, and ultimately getting in the way of investing in oil. And then—this is what surprised us the most in our supercycle thesis going out to 2028 and ’29—the energy transition itself will create the biggest demand shock for oil that we’ve ever seen.

The energy system needed to get the electrons to the consumer is so materials-intensive, so oil-intensive, that it could be the equivalent of China’s growth in the 2000s. The transition will create huge demand for oil, multimillions of barrels, which we can’t meet because the energy system is moving toward clean energy. That can exacerbate prices well above $200. It isn’t our base case, but I’m just giving you scenarios.

What do the rest of you make of that?

Croft: I broadly agree. It’s an interesting dynamic that has been playing out. We discussed the Saudi-Russia relationship earlier. If we think about the energy transition, lack of investment in energy in Europe, pressures around ESG investing, and what is happening in the U.S. shale basin, the last man standing is going to be the national oil companies in the Middle East. That raises a lot of questions about geopolitics, as well.

In the heyday of shale, we talked so much about American energy dominance and what that meant for U.S. foreign policy in terms of the ability to either retreat from a region like the Middle East or sanction countries we didn’t like, such as Venezuela or Iran, and shield U.S. consumers from the impact of that policy. We are in the waning days of American energy dominance. Yes, LNG is a big story and we are helping Europe meet its energy needs. But Saudi Aramco, Adnoc [Abu Dhabi National Oil Company], and Kuwait Petroleum are continuing to invest, and they dominate in production of oil.

Karim, you have written about these issues. Any further thoughts?

Fawaz: I would look at it a bit differently. In the early 2000s, we had capital available and a willingness to invest in supply, but we didn’t have the resource available [before the U.S. shale revolution]. In the current environment, we have the resource, but the questions are around capital and the willingness of companies to invest.

In the second half of 2021 and in 2022, organic capital generated by the energy industry created sufficient funds to invest in supply in the medium term. Midway through last year, a lot of people were of the view that even in a higher-price environment, companies wouldn’t increase capital spending. To some extent in the U.S., that was true as far as [shale] is concerned, although a lot of it was due to service-sector limitations and an inability to invest more even if companies wanted to. Yet, we saw the biggest global-exploration spending on record.

There has been underinvestment in energy production for the past decade. Some countries don’t have a lot of projects, but suddenly in the past 18 months they’ve had enough capital to invest. Outside of the Guyanas, Norways, and Brazils of the world—all big producers—production declined by about 600,000 barrels a day in 2020 and 300,000 barrels in 2021. It was flat last year. Capital has gone into existing operations. Over time, the compounding effect can really change the supply picture.

How would you size up demand?

Fawaz: The deceleration of demand matters more than the peak. A lot of people focus on when demand might peak. Is it 2028 or 2030? We think about the point at which the rate of demand growth starts to slow materially, and we see that starting in 2026-27 in a meaningful way, especially for products like gasoline and diesel and jet fuel.

If you think about it from a supply standpoint, the treadmill is slowing. In that context, the U.S. doesn’t need to be growing a million barrels a day per year to meet global demand growth. The U.S. needs to grow [supply] by 300,000 barrels a day per year because the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia have ambitious growth objectives.

In the medium term, we don’t see the ingredients to move into a sustained-scarcity world. We believe, however, that you need a significantly higher oil price than in the past decade. The shale-era price band of $45 to $65 is insufficient to meet demand through the medium term.

Lastly, China is a different element in the oil market that hasn’t existed in the past. It is a large consumer with slowing demand over the medium term, access to large inventories, and a willingness to swing imports depending on market conditions.

What are the implications of that?

Fawaz: The market avoided a catastrophic drawdown of oil inventories through last summer only because China took a three-month breather on imports of an average of about 2.5 million barrels a day. You now have an actor on the consumer side of the ledger that is able to regulate the upside in prices, to some extent.

Let’s transition to the energy transition. Given that all of you seem to see oil growing more expensive in the next few years, is this shaping up to be a lucrative last hurrah for the commodity?

Malek: The energy supercycle will last well into the 2030s. We will [have too little] oil well before we no longer need it. That lifts prices of old-economy stocks—of oil, gas, and even coal producers. We’re positioned bullishly in energy stocks that have a bias toward carbon and fossil fuels. It’s a relatively cautious moment if you have a six-month horizon, but those looking out over the next few years will want to prioritize companies that can grow their oil volumes. It is dangerous to say that this is the last hurrah, unless you define a last hurrah as 20 years. You want to own companies that can grow their joules of energy while decarbonizing and generating cash flow.

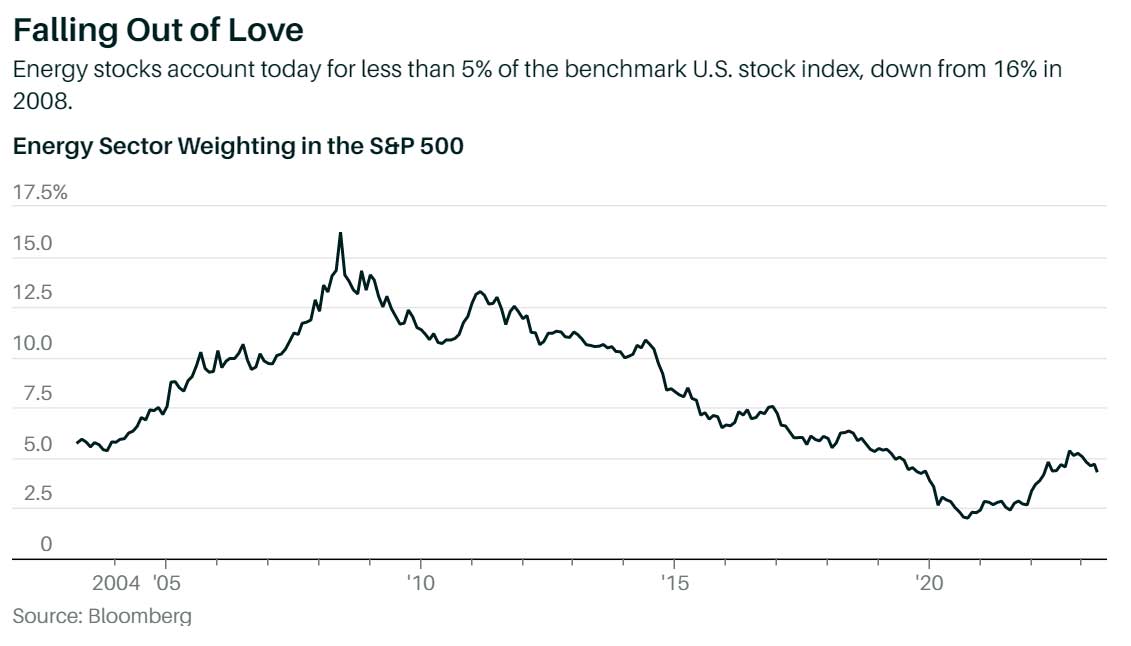

Energy accounts for 4% to 5% of the S&P 500. Should investors seek to double that exposure in their portfolios?

Malek: I would suggest at least 10%.

Would you put a significant portion of that in alternative-energy stocks?

Malek. No. Alternative energy and renewables are significantly overvalued. Returns are suffering because of cost inflation. Interest rates are going up. It’s almost like shale 2.0, where everyone is chasing growth and thinks about returns later. Returns will diminish and companies will struggle to deliver. It is likely that old-economy stocks re-rate higher as cash flow grows, and clean-energy stocks de-rate as delivery disappoints.

Croft: In the West, we are having one conversation on the energy transition, and the developing world is having a very different conversation. At COP 28 [the United Nations’ global climate conference scheduled for November], you’re going to see debates about what is the best transition. If you listen to conversations from Indian officials, from sub-Saharan African officials, they’re still focused on affordability. When millions of people use biomass to heat their homes, are you going to go immediately to solar? Or are you going to focus on what is the cheapest, most reliable form of energy? The developing world is an important driver of demand.

Dan, how should investors approach both conventional and alternative energy?

Pickering: They ought to be overweight energy. I recommend an 85/15 split between conventional and energy-transition names. The only reason you do 15% is to learn about the sector so you can spend a lot of time investing in it in the 2030s. It’s still too early. It’s the shiny new toy that is overcapitalized. The conventional stuff is trading for four to six times cash flow. Energy has been the best sector in the market for two years, but still has reluctant owners. The stocks are probably discounting $65 oil.

Will ESG concerns continue to weigh on the stocks?

Pickering: The ESG dynamic is probably plateauing, as well. The reality is, it was easy to hate these companies for the past couple of years because they burned you for five-plus years. They destroyed a lot of capital in the shale boom. When they’re returning cash and generating 10% to 30% free cash yields, it’s a heck of a lot harder to hate them. Some investors are never going to play. That’s OK, so the universe of buyers is smaller. But these companies are making money, and I expect that you will see investors gradually and grudgingly return.

Malek: I second Dan’s point on this. I meet with a lot of the CIOs [chief investment officers] in Europe. I asked one in Sweden, “At what point would you get involved in energy?” And he said, “Once it gets to 7% to 8% of the index, we have a problem. Then you are underperforming your own [stock market] benchmarks.”

There’s a pain threshold. It has been OK not to be in energy, because it has underperformed, so there has been no FOMO [fear of missing out]. But as energy outperforms, then it starts to become a larger part of the index and you can’t ignore it. Also, policy makers are realizing that the energy system needs a huge amount of current energy sources. So, the companies need to be requalified away from being bad to good. They become part of the solution. Those two things will converge within the next two or three years. They are around the corner.

What needs to happen for these areas to be investible?

Pickering: It’s really the time it is going to take to move these companies toward profitability. Some have raised enough money to be able to make it to profitability, but it’s the process of getting there. In the meantime, you’ve got a bunch of companies that are going to go broke.

To wrap up, what might surprise people in energy over the next year?

Malek: As I said, demand is king. And it could disappoint. What a cocktail we’re facing: higher mortgage rates, expensive everything. My biggest worry is that China could become very different socioeconomically, industrially, behaviorally than it was previously, and it doesn’t really catch up [to its previous trajectory]. In that case, we can talk underinvestment all day long, but it will take a while before that deficit materializes, ultimately because demand disappoints.

Croft: We are into the second year of the Russia-Ukraine war. We have become so complacent. Even in Washington, the view is that Russia played its cards, and is a spent force. What would surprise us is a decision in Moscow to cause significant economic pain for the West—that they aren’t done. We shouldn’t take off our radar the possibility that Russia still tries to change Western calculations about continued support for Ukraine. As long as the West continues to supply Ukraine with more weapons, the war from Russia’s standpoint is difficult to win.

Pickering: I have four potential surprises. The demand side can surprise us. I’m estimating $80 oil. If it’s $60, something happened with demand—we didn’t have a moderate recession; we had a severe recession. The second follows on Helima’s comment about Russia, although I’d take a different tack. If peace breaks out, oil goes down. It probably shouldn’t, but it will, at least in the near term. If peace breaks out, that could be surprising.

I also wrote the word stagflation. If inflation is stickier than people think, oil is likely a contributing factor and investors will be making inflation plays. Energy would certainly be a part of that trade. Lastly, what if we see a wave of takeouts? Those would be four potential surprises, none of which are in our base case.

Karim, what’s on your mind?

Fawaz: To echo a lot of what has been said already, demand is still the biggest concern in the short term. In terms of something harder to visualize, the past 12 months, especially 2022, was the year of intense government intervention [in sanctioning Russian oil and more]. To some extent, that slowed down over the past four months. There’s a sense of complacency that we went through this wave of intervention and now we’re normalizing. But the reality is, you can end up in a pre-interventionist environment pretty quickly if markets break out of this quasi-comfortable range. If prices move closer to $100 a barrel, does the U.S. administration change the way it is thinking about these things—and vice versa on the downside? OPEC countries have significant modernization needs, so how that friction emerges in the next two years is also going to be interesting.

I was just in New York and Boston, talking with a lot of our investor clients. This is the first time in 10 years that I didn’t get a single question about U.S. shale. That is interesting to me. To some extent, U.S. exploration and production companies have succeeded in making themselves boring and stopped being disrupters, which they have wanted to do for a number of years. But this system is still dynamic. This year is difficult, but over the next couple of years, you might start to see more comfort with potentially moving from 0% to 5% [production growth] to 3% to 7% production growth. You might also see consolidation in the hands of producers that are more comfortable growing than the current operators. We’re one U.S. supply overshoot away from supply abundance getting back in the narrative. It’s a low-likelihood outcome, but if the U.S. overshoots one more time, it’s difficult to see how this sector gets on a sustainably more bullish trajectory in the medium term.

That’s a lot to think about. Thank you, all.

This content originally appeared in an article in Barron’s titled, “Our energy roundtable predicts higher crude prices as global demand grows. What’s ahead for shale, energy transition.” published on May 19, 2023.