Key Points

- As the war in Ukraine enters its second year, a key question for market participants is whether Russia’s disruptive power is diminishing or whether it still has the capacity to cause significant pain for Western consumers by curtailing energy supplies. Has Moscow already played all of its strong cards by turning off the gastapsto much of Europe and in turn providing the catalyst for countries like Germany to seek new sources of supply and fast track the buildout of critical LNG infrastructure? Does President Putin have any real economic option but to continue to sell oil at depressed prices in order to maintain the principal funding stream for his war machine? Or, have we merely entered a fleeting period of calm as the Russian president prepares for another brutal winter campaign—with energy as an essential weapon—to test the resolve of the West to continue providing military and financial support for Kyiv?

- Despite Russian causalities topping 70,000 and a projected 3.4% GDP contraction in 2023, President Putin shows no signs of abandoning his maximalist goals and seeking a negotiated settlement that would be acceptable to Ukraine. At the same time, there are questions about what remaining cards Washington is holding if there is another surge in energy prices due to the war and/or a full China reopening. Having already drawn down over 200 million barrels from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve, it would appear that the White House would fall back on the long standing strategy of seeking additional barrels from Saudi Arabia and the few remaining Gulf producers that hold spare capacity. However, if we have learned anything from this year, the interests of Washington and the OPEC nations are not always aligned and a failure to connect can trigger recriminations.

- For now, OPEC looks content to stick with the headline 2 mb/d production cut and to stay above the political fray. And yet, if market conditions were to materially deteriorate because of rate hike and recession concerns, OPEC can likely be counted on to seek to put in a price floor. Prince Abdulaziz has repeatedly signaled a willingness to make quick course corrections in order to ensure market stability and safeguard national interests. While he is maintaining a poker face at the moment, the Saudi oil minister is not seemingly out of cards.

- Finally, the return of Benjamin Netanyahu to power represents a major geopolitical wildcard for the oil market as he has promised to put Iran at the top of Israel’s policy agenda.

Expiring Date for the Energy Weapon?

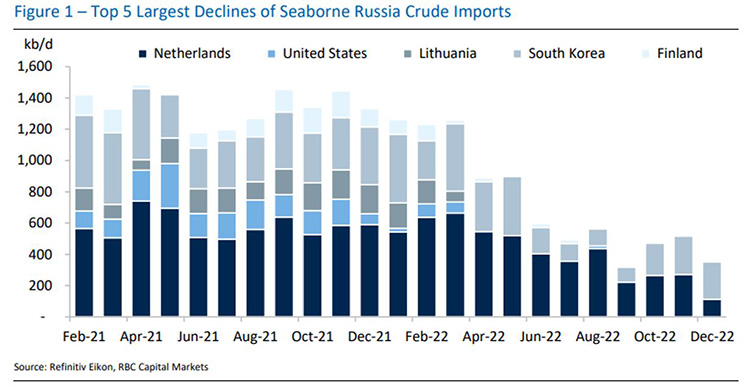

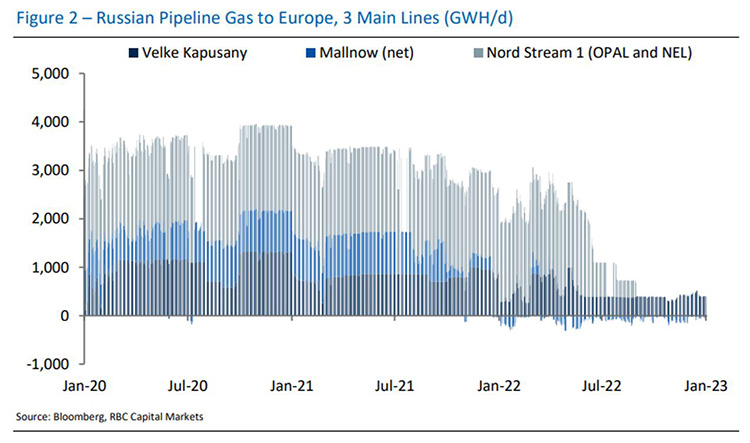

To date, the Biden administration has largely achieved its overarching goal of keeping Russian oil largely on the market, while sanctioning other sectors of the economy and the military industrial complex. Senior US security officials contend that the export restrictions on critical components such as chips have been especially effective in degrading Russian military capabilities, with Moscow reportedly resorting to repurposing semiconductors from washing machines. These supply challenges, as well as deepening morale problems, could complicate Russian efforts to launch a spring offensive. Nonetheless, officials in Washington maintain that there are no indications that Putin is backing down from his overall objectives and that he will seek to make winter as punishing as possible for Kyiv and its key Western sponsors. Being the third largest producer of oil and the second largest natural gas producer, energy was always going to be one of Moscow’s biggest leverage points. From the start of the conflict, Western leaders signaled a clear concern about higher energy prices through sanction carve-outs and long lead timelines for the implementation of coercive measures such as the EU ban on seaborne oil imports. Russia has already made good on its threats to disrupt gas supplies, with piped flows to Europe currently down over 85% y/y. As we have noted previously, gas has long been a weapon of choice for the Kremlin given Europe’s high dependence on Russian supplies as well as its more modest revenue-generator role. Certainly, the remaining Russian gas flows through Ukraine would seem to be at elevated risk for curtailment, especially given the ongoing aerial bombardment of Ukraine’s energy infrastructure. With storage levels in Europe remaining relatively robust amid mild weather conditions, the real challenge for the continent on the gas side could come towards the tail end of 2023 with no additional Russian volumes likely forthcoming.

Oil is a trickier card for Putin to play because of its centrality to state coffers. The architects of the G7 price cap plan essentially wagered that Russia would have no option but to keep supplying that market at the $60 price point if it wanted to continue with the war effort. And yet, President Putin at least continues to mount a rhetorical resistance to the price cap, pledging to cut supplies to any customer that participates in the plan from February onwards. Last week’s presidential decree, which came three weeks after the scheme was launched, was short on details and it is not clear what constitutes participation in the initiative. For example, is signing the price attestation the key criteria for a cut off or is using the cap to bargain for better pricing grounds for a supply suspension? Putin has also seemingly left himself wide authority to issue waivers for strategic considerations. India will likely be a key test case of Russian resolve to see this pledge through as the country has emerged as the principal purchaser of distressed Urals barrels no longer welcome in the West. While Prime Minister Modi and Petroleum Minister Hardeep Singh Puri have publicly voiced opposition to the G7 plan, its refiners are still largely dependent on Western service providers to obtain their cargoes. Early indications are that these customers are continuing to avail themselves of Western services and therefore are presumably signing the requisite attestation that they were purchasing the barrels at or below the $60 cap.

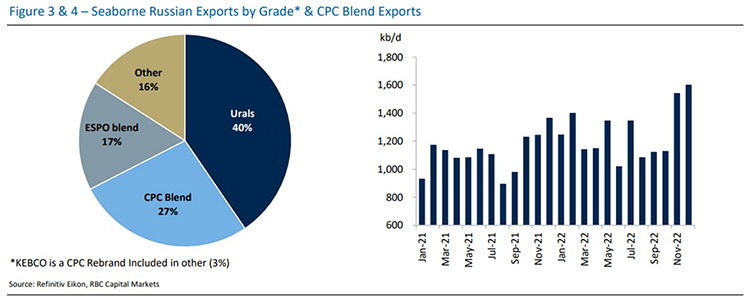

We certainly see scope for Russia to engage in some symbolic export suspensions in order to create doubt about the viability of the G7 effort and attempt to drive oil prices higher. Unlike with gas, however, we think that the Russian leadership will be much more strategic with their oil curtailments given the clear revenue imperative. Deputy Prime Minister Alexander Novak’s comments about a 5-7% reduction seemingly signals that supply restrictions will be deployed more like a scalpel than a blunt instrument. Moreover, we could envision a scenario where the Kremlin seeks to rebrand disruptions due to compliance challenges and service provider problems as a deliberate policy choice. At the time of writing, we estimate that seaborne exports have fallen over ~20% m/m in December, with lost flows primarily coming from Urals and ESPO grades. Even in the event that a deep oil supply disruption is averted, the decision of Western planners to prioritize inflation reduction over Russian revenue reduction may pose risks for the war effort. Critics contend that setting the cap at a level close to market price for Urals—thereby keeping a critical revenue stream largely intact—Western planners are potentially setting the stage for a forever war scenario.

Another concerning scenario would be for Russia to disrupt oil supplies from other producers through sabotage or interference in internal affairs. There have already been a number of suspicious CPC pipeline outages. In March of 2022, loadings of Kazakh crude from the CPC were suspended at the Russian port of Novorossiysk, with Russian officials citing weather related damage to loading berths as the cause for the weeks-long outages. However, senior energy officials from other governments have suggested that Moscow may have had an active hand in the CPC outage as part of a test run of its asymmetric disruptive capabilities. Hence, we would put CPC flows close to the top of a 2023 risk list.

Similarly, leading security experts contend that Russia has the ability to disrupt supplies from countries where the FSB and Kremlin-linked mercenary groups maintain a significant presence, such as Iraq, Algeria and Libya. Given that Washington has strongly signaled an aversion to higher oil prices, and has gone to quite extraordinary lengths to keep a lid on them, there remains an elevated risk that Putin will seek to exploit this pain point in 2023 even if it is principally through asymmetric action. Moreover, a case could be made that Moscow’s peak leverage point may be in the coming cold months and once the green shoots of spring appear, many in the West may conclude that the worst is over from an economic warfare standpoint. Hence, our view that we may be entering a particularly precarious phase in the conflict and that President Putin may endeavor to demonstrate that he is not a spent force.

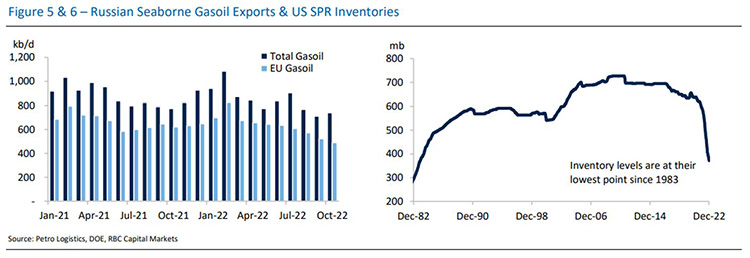

One crucial test for markets will come after the February 5 EU ban on the importation of Russian refined products. We have consistently maintained that the products ban will be more difficult to mitigate than the seaborne oil embargo. Asia has been the key release valve for crude, with India taking over 900 kb/d more vs historical levels. Even then, both China and India have seen m/m decreases in crude volumes last month following the embargo. There is no India market equivalent for seaborne diesel shipments, so a mass switch in crude supply like the one we saw with Asian refiners following the invasion is less likely. Moreover, replacing displaced product imports in Europe will also be more difficult given tight product markets; ~500 kb/d of diesel imports were still coming from Russia into the EU in October.

Waiting in the Wings

In addition to making it a top policy priority to keep Russian oil on the market, Washington also made unprecedented use of the SPR to shield US consumers from pain at the pump. The Biden administration releases of over 200 million barrels marked the first time that the SPR has been used explicitly to lower prices in the absence of a major global supply disruption. We do not envision that there will be another blockbuster release in 2023 with the SPR now standing at the lowest point in nearly 40 years and senior administration officials signaling an intention to commence the repurchase effort. Hence, in the event that prices do move appreciably higher because China completely jettisons the zero-Covid policy or because of geopolitically-driven supply disruptions, the White House would likely engage in another round of telephone diplomacy with the key OPEC members and we see the producer group gaining enhanced leverage in the year ahead. Relations between Washington and Riyadh have seemingly recovered from the post-October 5 meeting lows, as it appears that the White House has walked back its threats to impose consequences for the 2 mb/d headline production cut. The fact that the post-meeting price rally was modest and the Democrats exceeded expectations in the mid-term elections undoubtedly helped mollify the Biden administration. For now, OPEC looks content to stay the course on the current production policy and is seeking to stay out of the confrontation between Russia and the West. Nonetheless, we see clear scope for OPEC to adjust the production cut if demand concerns were to deepen because of a global recession or a catastrophic public health crisis in China. Even though the next scheduled OPEC meeting is not until June, the JMMC will be meeting every two months and has the authority to request a full ministerial meeting at any time to address market developments if necessary. We believe that Prince Abdulaziz will continue to pursue the dual mandate of providing market stability as well as the economic enabling environment to fulfill his country’s ambitious Vision 2030 development agenda. While we think Riyadh will continue to take the call from Washington, the leadership will not sacrifice their national self-interest to ensure that US drivers pay less than $4 per gallon.

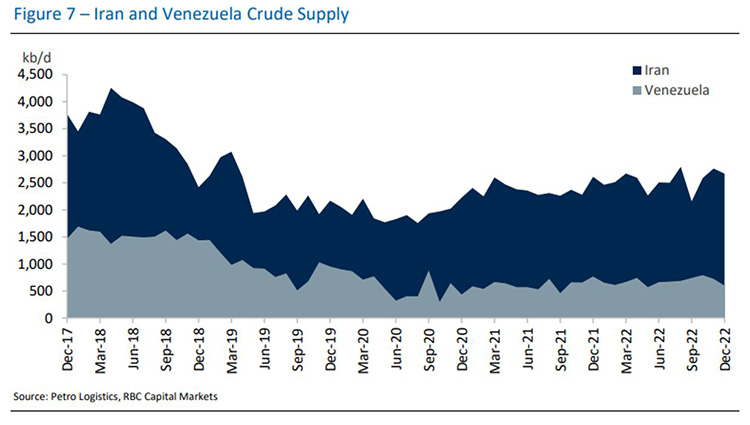

Relaxing sanctions on key oil producers would also provide scope for more barrels to make their way to the market, but the politics remain fraught for the Biden administration. The White House has already lifted some energy sanctions on Venezuela, such as allowing Chevron a temporary license to resume drilling in the country, but the Maduro government will need to make much deeper electoral and governance reforms ahead of the 2024 elections for more material US financial relief. The White House’s room to maneuver in the absence of such reforms remains circumscribed as a number of influential US senators remaining staunchly opposed to making additional concessions to President Maduro (who was indicted by the US Justice Department in March of 2020 for “narco-terrorism” and other corruption-related offenses). The full-scale revitalization of the Venezuelan oil sector in return will likely require billions of dollars in new investment as well as one of the most complicated international debt restructurings ever undertaken. As we have noted on multiple occasions, the crisis in Venezuela has been decades in the making and the situation on the ground is akin to a post conflict environment. Hence, the lifting of sanctions will not serve as a light switch that will enable an immediate surge in output beyond a potential incremental gain of a couple hundred thousand additional barrels a day.

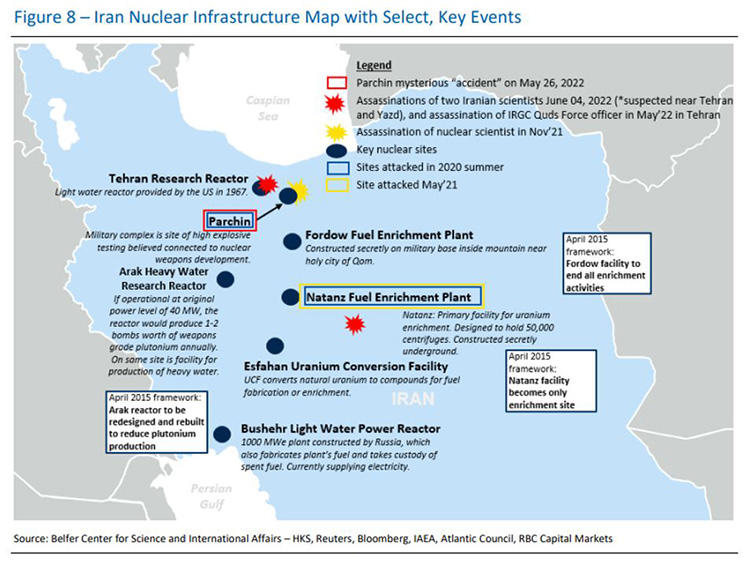

If Venezuela still represents the art of the possible from a sanctions relief perspective, Iran no longer represents a source of near-term production growth as the prospects of a diplomatic breakthrough in the nuclear talks have essentially flatlined. Iran has essentially become a nuclear threshold state by amassing such a large stockpile of highly enriched uranium that it would need almost no time to achieve breakout capability and make the final push to producing weapons-grade fissile material. Even if Iran were to reverse all of these nuclear activities and become fully compliant with the 2015 JCPOA agreement, Biden would likely face withering congressional criticism for providing the Iranian regime any financial windfall given the regime’s brutal crackdown on demonstrators and provision of military support to Putin.

Finally, Benjamin Netanyahu’s return to power represents the biggest geopolitical wildcard in our view, as it will lead to a much more muscular Israeli response to Iranian nuclear advances. Netanyahu has vowed to place Iran at the top of his agenda and he is leading one of the most hawkish governments in the country’s history. His incoming head of the National Security Council, Tzachi Hanegbi, predicted last month that Netanyahu would order a strike on Iran if the US fails to neutralize the nuclear threat, telling local news reporters that the Prime Minister “will act, in my assessment, to destroy the nuclear facilities in Iran.” Even if Netanyahu opts against a direct attack on the nuclear sites (potentially because of White House opposition), we think it is highly likely that he will turbocharge the covert action campaign, which could in turn lead to an escalatory spiral that could end in a confrontation between Israel and Iran. If 2022 taught us one thing, it is not to write off the risk of a war that seem illogical from the standpoint of many market participants.

Helima Croft authored “2023 Geopolitics Preview: Wartime Sky,” published on January 2, 2023. For more information on this commentary or to access global commodities research, please contact your RBC representative.