The growing momentum for Net Zero

As public sentiment, private capital and political commitments continue to evolve across the Energy Transition debate, so has the narrative regarding the role of Carbon Capture and Storage (“CCUS”) in achieving the binding Net Zero targets, communicated on both the national and corporate stage.

With over 30% of global investors mandated to invest in ESG and over 70% of investors using ESG principles as part of their investment decisions (RBC’s Global Asset Management Responsible Investment Survey of over 800 investors) the need for companies to adapt to the new realities is very clear.

Martin Copeland, Managing Director and Head of Energy in Europe, examines the state of play for CCUS as an essential component to achieve Net Zero emissions by 2050.

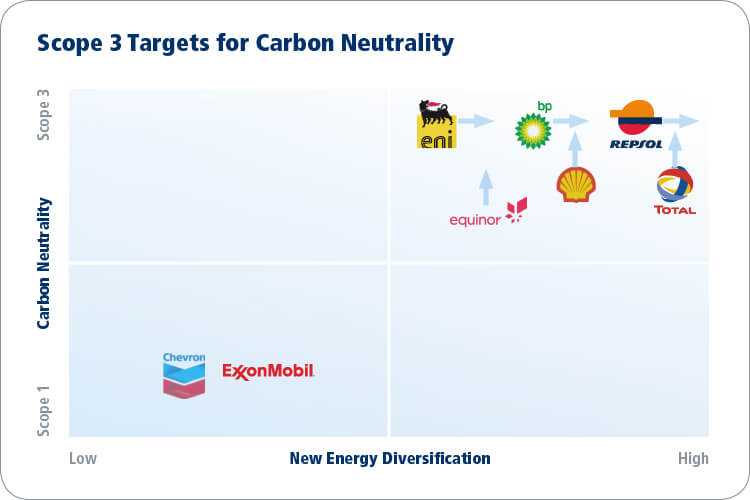

The diagram below highlights the extent to which the European Majors (unlike their U.S. peers) have not only adopted Scope 3 targets for carbon neutrality (i.e. not only responsibility for their own emissions, but also for the emissions caused by their products when used by consumers), but are also moving to transform their businesses through diversification into New Energies. None of these goals can be achieved without CCUS playing a material role. CCUS will increasingly become a critical component of the licence to operate for global oil companies.

Source: Wood Mackenzie

Source: Wood Mackenzie

CCUS in the mix

Given the vast challenge of tackling climate change and the practical and economic challenges of replacing hydrocarbons for all uses, the importance of physically removing carbon from emissions, and potentially directly from the atmosphere, is becoming increasingly recognised as an essential part of the solution.

The inconvenient truth, not often cited by the more radical end of the climate activist community, is that oil and gas are extremely efficient and cheap stores of energy. If we consider the entire 14GW installed and FID’d generating capacity of the largest pure play windfarm company Orsted (Market Cap $58 billion), that is only the energy equivalence of just over 200,000 Barrels of Oil Equivalent per day.

To put that in perspective, this is comparable to small / midcap E&P companies such as Norwegian midcap Aker BP (Market Cap $6 billion). The energy density advantage of hydrocarbons means they will remain a long term future requirement for sectors such as heavy transportation and aviation. In addition the need to integrate gas fired power with wind and solar to offset the inherent intermittency of renewables is becoming increasingly recognised. The use of oil as a feedstock for plastics and petrochemicals adds another long-term continuing demand driver for conventional hydrocarbons. However, society will increasingly demand the achievement of Net Zero hydrocarbons and this will inevitably require offsetting, either through nature sinks and/or through CCUS.

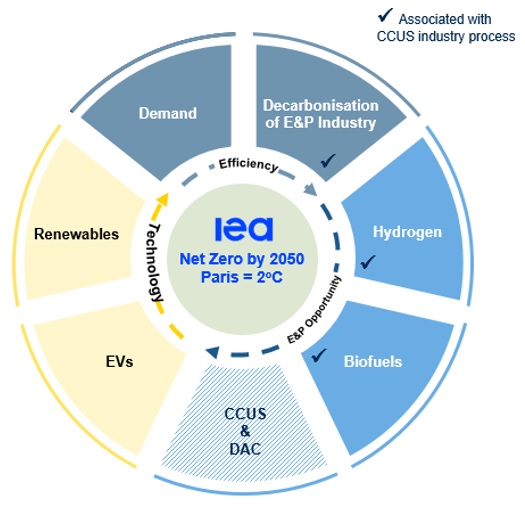

Analysis by the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (“IPCC”) and International Energy Agency (“IEA”) has consistently shown that CCUS is an essential part of the lowest cost path towards meeting climate targets. Kwasi Kwarteng, UK Minister of Energy commented in August 2020 that “CCUS will be a crucial part of our green recovery. It is essential that we act now to put ourselves on track to meet our Net Zero emissions target by 2050, as well as driving growth across the UK.”

CCUS 2.0

The technologies behind the capture, transportation and storage of CO2 are well proven and have in fact been in operation at scale since at least the 1990s. CCUS is being used extensively today around the world, predominantly in North America where CO2 flood (albeit not always anthroprogenically sourced) is used extensively to increase hydrocarbon recovery from oilfields, known as Enhanced Oil Recovery (“EOR”).

Despite this track record, a massive increase in what we at RBC term “CCUS 2.0”, or the capture and sequestration of CO2 purely for the purposes of offsetting emissions, is still required if we are to achieve the announced global climate change commitments.

The key challenge to delivering the CCUS 2.0 required is that this offsetting activity is, by its very nature, not inherently economically value creating. Developing new value chains to generate alternative sources of associated revenue, such as so-called “blue” Hydrogen (combined with CCUS), as well as well-crafted subsidy and tax incentive regimes, will be crucial to driving the uptake required to achieve the world’s Net Zero goals.

A collaborative effort is essential

The absolute priority and likely trajectory for the early 2020s is therefore the development of new business models and integrated public to private sector partnerships. Given the scale of the challenge and the capital commitment required, we believe that the application of business models, in many cases adapted by modifying those successfully applied to catalyse the wind and solar industries over the last decade, will be required. This in turn will likely create a new infrastructure investment class to help drive the CCUS industry as part of a new energy value chain.

Today, CCUS technologies capture around 35Mt of CO2 emissions. However, the goals laid out in the IEA’s Sustainable Development Scenario require CCUS to capture 2,400 Mt CO2 by 2040 and account for 7% of emissions reduction globally. This seventy-fold increase is an enormous technical and financial undertaking, required to be implemented in short order and accelerated over the next 20 years.

At present, the UK and EU lag behind the U.S. on dedicated CCUS policies and financial incentives. Many details of the EU’s Green Deal, as it applies to CCUS, are yet to be determined. Transforming business models to catalyse the commercialisation of CCUS 2.0 will require a collaborative approach between Governments and corporates on an international scale. It will also rely on an integrated energy policy, both nationally and regionally, to enable various forms of legislative support, required for CCUS to attract capital and importantly to allow for cross border transfers of CO2 from key emitters to suitable subsurface storage locations.

Effective Carbon Pricing is also key to establishing the commerciality for “CCUS 2.0” projects. Current estimates of the levels required to drive commerciality remain wide, with French Oil Major Total modelling a carbon price of $100/Mt required by 2030 compared with Shell’s view that at least $235 is required by 2050 to make the required amount of CCS economic. The political will to implement these levels of carbon taxing and the details of how such carbon taxing will apply, especially given the need to ‘reboot’ economies in a post COVID world, will remain one of the key challenges to the pace of adoption of CCUS. Despite the rhetoric from the White House, the United States’ federal 45Q tax credit, which provides $35/Mt for CO2 sequestered during EOR or $50/ Mt for CO2 which is simply stored, is probably the most advanced global policy to incentivise CCUS.

Meeting the legally binding obligations of Net Zero and the corporate targets which have come thick and fast this year will require massive leaps in the amount of CO2 sequestered globally. Ensuring that the capital required for this ‘giant leap’ is effectively mobilised will require creative combinations of public and private partnerships and the ingenuity of funds, banks and governments in the coming years.